Democracy in Cuba: Spotlight on the 2018 elections

Lauren Collins | Tuesday, 6 March 2018 | Click here for original article

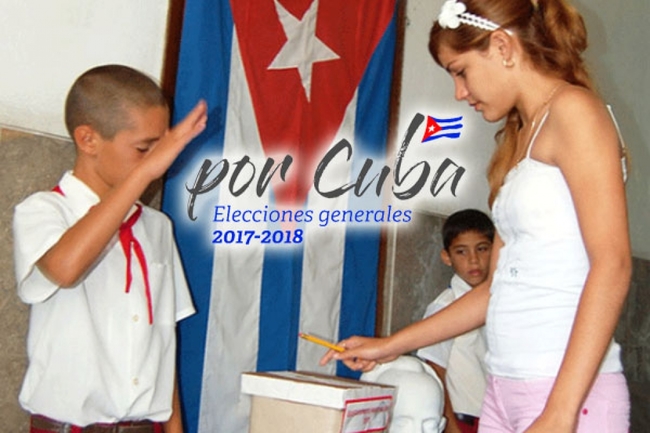

The North American and European mass media pay scant attention to Cuba’s general elections, which usually only warrant a few sentences seemingly written for the sole purpose of pointing out that they hardly qualify as elections at all. But with President Raúl Castro’s announcement in 2013, that he will not accept nomination to the presidency in 2018, we can expect the spotlight to be shone on these elections as never before. CubaSí published two articles - both articles are included below - which explain the Cuban election process and the participatory nature of Cuba’s governmental system.

Municipal delegates and popular participation

In early 2018, all Cuban citizens over 16 years of age will elect their representatives to the National Assembly (Cuba’s parliament), and to the sixteen Provincial Assemblies.

The election is the culmination of thousands of meetings and activities during the preceding months, involving millions of Cubans. Cuba’s system of government, known as People’s Power (Poder Popular), has three tiers made up of the National Assembly, sixteen Provincial Assemblies, and 169 Municipal Assemblies.

The National and Provincial Assemblies are elected every five years, and because they are made up of up to 50% of local delegates from the Municipal Assemblies, local elections are an essential part of the general election process. This is very different from the system in the UK, where local council elections have no bearing on parliamentary elections. Another distinctive feature of the Cuban system of government is that elections are only part of the picture. The involvement of all citizens, not only in the process of elections, but in all aspects of government between elections, is an essential part of Cuba’s participatory system.

The election of 12,515 municipal delegates to the 169 Municipal Assemblies will take place on 26 November 2017, although the process of communities choosing the candidates who will appear on the ballot papers has already begun.

Each of the 169 Municipal Assemblies are made up delegates who have been nominated and elected by the community they represent, with each delegate representing an average of 1,000 voters. The number of delegates that make up the Municipal Assembly varies depending on the size of the population. For example, the Municipality of Mantua, in the province of Pinar Del Río, has a population of 26,000, while the Municipality of Santa Clara in Villa Clara Province has a population of 215,000. The exact size of the Assemblies differ slightly from election to election, depending on changes to the size of the population, but Mantua will have around 30 delegates while Santa Clara will have around 167.

How are municipal delegates nominated and elected?

In the run up to the municipal elections, each electoral district (in the UK we refer to these as ‘wards’) is divided into between two and eight smaller areas for the purpose of holding nomination meetings to choose candidates. This means that most people at the meetings are neighbours and know each other. There will have been 45,688 meetings held throughout the island by 30 October. At the time of writing (9 October 2017) 35,941 persons have already been nominated in 25,844 meetings, which have been attended by 79% of the electorate. Of those nominated so far 17,000 (35.59%) are women, and 65.1% are not currently serving as delegates.

Anyone attending their nomination meeting can put forward the name of a person who they believe would make a good delegate, but the person must be resident in the ward, and must agree to being nominated. People cannot nominate themselves: it must be the community who put forward who they think is best suited to the role. The person putting forward the name must say why they think the person would make a good delegate. In practice, several names are put forward, and then the meeting discusses the merits (and de-merits) of the proposed candidates.

After discussion, everyone at the meeting votes to choose who, from amongst the people proposed, they want as their candidate. Each of the meetings in the ward selects a candidate in the same way, and consequently, there will be between two and eight candidates on the ballot paper on the day of the election.

To be elected to represent the ward at the Municipal Assembly, the winning candidate must receive at least 50% of the vote on Sunday 26 November, when there will be 24,000 polling stations across the country open from six in the morning until six in the evening. If no candidate achieves more than 50% of the vote, then a run-off election between the two candidates with the highest number of votes will be held on the following Sunday (3 December). Any member of the public can attend the counting of the votes which happens immediately after the polls close.

The method of choosing candidates is obviously very different to the UK system, where the names on the ballot paper are chosen by political parties, and the public in general has no say in who the candidates are. In Cuba, the Communist Party (the only political party) plays no part in the process of nominating candidates: the community decides who will be on the ballot paper.

Another significant difference between Cuban and UK elections is the absence of election campaigning, which, in the UK and elsewhere, is chiefly based on the competition for electors’ votes between political parties on the basis of election promises and policy manifestos. Cuba’s political system is one based on public participation, and policy formation is done on the basis of deliberation and discussion. The notion of elections being the site of policy debate is an anathema to Cuban political culture, which seeks inclusion and unity.

What is the role of the municipal delegate?

The municipal delegate is a member of the community that elected him or her, living and working in the neighbourhood that they represent. Most delegates remain in their usual employment and carry out their role on a voluntary basis. Those delegates who take up full-time roles (the president and vice-president of the Municipal Assembly for example) are paid at the same rate as their usual day-job, which is held open for them for when they cease being full-time delegates. This means that elected delegates do not become separated from their electors and continue to share the ups and downs of daily life with them.

The duties of an elected delegate are regulated by law. Every delegate must hold a surgery at the same time and place every week so that individual residents can meet privately with their delegate to ask for help and support in resolving any problems they may have in relation to the local administration, or any of the public services and industries for which the Municipal Assembly has responsibility. In addition to weekly surgeries, delegates must hold regular public meetings with his or her electors to report on the work of the Municipal Assembly, explaining local policies and decisions. At these meetings (known as ‘accountability meetings’) voters are expected to report problems that they encounter with public services, and delegates are duty-bound to follow up every single report, suggestion or complaint.

Since the 1990s, aside from the formal accountability meetings, more frequent, more local, and therefore smaller and less formal meetings are held to encourage greater participation on behalf of the citizens, and to foster a closer relationship between the delegate and his or her electors. These meetings, however, are not just ‘talking shops’. Every suggestion, report or complaint, is carefully recorded, and collated at the municipal, provincial and national level. This body of information is then used to make evidence-based decisions about resource and budget allocation, and informs policy-making.

Without the active participation of the public in these meetings, the quality of decisions at all levels of People’s Power would be compromised, and the policy-making would be less effective. This is one important way in which the public participate in governmental affairs.

Popular Councils

To bring government closer to citizens and to provide further opportunities for participation, in 1988, an additional level of government was added to People’s Power: the Popular Councils (Consejos Populares).

Immediately following the municipal elections, the Municipal Assemblies establish Popular Councils throughout their municipality. For example, in the Municipality of Mantua, there are nine Popular Councils, each one of which groups together several wards. Each Popular Council is made up of the delegates of the wards concerned together with representatives from the local mass organisations, that is Committees for the Defence of the Revolution (CDR), Central Union of Cuban Workers (CTC), Federation of Cuban Women (FMC), and the Association of Small Farmers (ANAP).

The Popular Council can also invite others to join the Council where the delegates think it helpful for resolving problems, or improving services, for example health workers, managers of local factories or farms, teachers from local schools, social workers etc.

Since the Popular Councils became incorporated into the Peoples’ Power system in 1992, responsibility for the day-to-day oversight of many services and production centres has been devolved to them from the Municipal Assembly. This has meant that the Municipal delegates have been able to work as a team for the communities they serve, and also, importantly, the Councils provide citizens, through their mass organisations, with the opportunity to support, the work of the elected delegates. This style of working means that communities are able to prioritise the work of the Popular Councils, identify local resources, collectively develop plans for their communities, and request support from the Municipal Assembly. For example, plans might include identifying the need for an additional medical centre, facilities for young people, or extra places at day-care centres for senior citizens.

In the Cuban system there are strong links between local government and the Provincial Assemblies and the national government. Up to 50% of Provincial Assembly and National Assembly representatives are also municipal delegates. Municipal delegates are at the heart of a system of government which depends on popular participation.

Approximately, one in every 1,000 people is serving as a municipal delegate at any one time, and, with an average of 50% new delegates returned at each local election (held every two and a half years), a significant number of citizens have experienced incumbency. Elections are not events where the citizens’ relationship with government starts and ends. Frequent interaction between the electors and their delegates, and membership of the mass organisations create close contact between the Cuban people and their government in the neighbourhoods where people work and live.

The Revolution’s approach to democracy is one in which voting is just one part of a system that depends on the involvement of the whole population in the business of government.

On 19 April 2018, Cuba’s newly-elected National Assembly (Cuba’s parliament) will convene. One of its first responsibilities will be to elect the next President of the Republic of Cuba. Elections to the National Assembly, and to the 16 Provincial Assemblies, are always preceded by local municipal elections.

National Assembly of Popular Power

On 26 November 2017, 12,515 ordinary citizens were elected to serve on the country’s 168 municipal assemblies. By law, the National Assembly must made up of up to 50% of elected municipal delegates. This is one of the ways which ensures that Cuba’s national parliament does not become a ‘Havana Bubble’. Having municipal delegates serve in the national parliament creates strong links between the highest governmental body and the communities it serves. Of the current 612 deputies (as those elected to the National Assembly are known), 284 are elected municipal delegates which is 46.41 % of the total. Women make up 48.86 % of the Assembly, and 37.09% are black or mixed-race. The average age of deputies is 48 years, and 45% are members of the Communist Party of Cuba.

The National Assembly is the only body in Cuba which can enact legislation. To carry out its duties effectively, it has the following structures: Council of State, Council of Ministers, and Work Commissions.

Council of Ministers

The Council of Ministers is effectively ‘the Government’. It also comprises the First Vice President, the Vice Presidents, and the Ministers which head up the various government departments; 32 members in all. The Council of Ministers organises and directs the execution of the political, economic, cultural, scientific, social and defence activities agreed upon by the National Assembly of Popular Power. Also amongst its responsibilities are: directing the foreign policy of the Republic and relations with other governments, proposing the projects of general plans of economic-social development, and preparing the draft budget of the State and once approved by the National Assembly of People's Power, ensuring its implementation. It is worth noting here that (in 2017) 72% of the current expenditure of the State is allocated to basic social services (quality of life of the population and social security benefits). This is an indication of the importance of the work of the National Assembly to the everyday welfare of the entire population.

Council of State

The Council of State is roughly akin to a ‘cabinet’, in that it is responsible for carrying out decisions of the National Assembly, between full sessions of the National Assembly. It is, effectively, the ‘executive’, because it carries out decisions made by the whole Assembly. It is collegial in character, that is, it makes decisions, and takes responsibility, collectively. It can decree laws between sessions of the National Assembly as necessary, but these must be subsequently ratified (or not) at the next full session of the Assembly. The Council of State reports to the National Assembly. Along with the mass organisations (Committees for the Defence of the Revolution, Central Union of Cuban Workers, Federation of Cuban Women, and the Association of Small Farmers), the Council of State can initiate legislation, although legislation itself can only enacted by the National Assembly. The Council of State appoints the Council of Ministers.

Work Commissions

The National Assembly also establishes work commissions, comprised of ordinary deputies, and ministers, which assist the National Assembly and the State Council. Their role is to carry out studies and research to support policy-making and the drafting of legislation, and to participate in the verification of compliance with the decisions adopted by the National Assembly and the Council of State. There are ten commissions in all which include those for national defence, industry, construction and energy, food, health and sport, the economy, and children youth and the rights of women.

Commissions comprise an average of 33 delegates. Although the National Assembly do not meet as often as parliaments in the Europe, the hard work goes on in these work commissions. They hold extensive public consultation as part of their deliberations, and policy and legislative proposals are worked through in detail prior to being presented at National Assembly sessions. This explains why many votes are unanimous. The debates and discussions mostly take place outside the legislative chamber, in the commissions and in the country.

How are the National Assembly deputies elected?

The new National Assembly will consist of 605 deputies. It has been announced that the new Provincial Assemblies will be constituted on 25 March and the National Assembly will be constituted on 19 April 2018, following the general election on 11 March. The elections to the Provincial Assemblies, and the National Assembly take place on the same day. Hence, on 11 March 2018, voters will have candidates to their Provincial Assembly, and to the National Assembly, on their ballot paper. The number of names on the ballot paper will be equal to the number of delegates that are to be elected. The fact that there is no ‘choice’ on the ballot paper (that is the elector does not choose who they consider most suitable for the role of deputy from several names on the ballot paper) is, of course, cited by many commentators outside Cuba as being ‘proof’ that Cuba’s electoral system is not democratic. However, the processes by which names are placed on the ballot paper is extensive and inclusive, and we shall now examine these processes.

Candidacy Commissions

Candidacy Commissions play an important role in selecting candidates to the Provincial and National Assemblies. Each of the 168 municipalities creates a Candidacy Commission, as do each of the 16 Provinces. There is also a National Candidacy Commission. Each commission is made up of representatives from the following six organisations: Committees for the Defence of the Revolution, Central Union of Cuban Workers, Federation of Cuban Women, and the Association of Small Farmers, the Federation of University Students, and the Mid-Level Students' Federation and each is chaired by a Trade Union member. These six organisations decide themselves who will represent them on the Candidacy Commissions. It is noteworthy that young people are involved in this process through the two student unions.

The role of the Candidacy Commissions is to receive proposals from the public, via their mass organisations, as to who should be on the ballot paper when the elections to the National Assembly take place. Proposals are made in full open meetings (plenary sessions) of each of the mass organisations in all municipalities and provinces, and then forwarded to the relevant Candidacy Commission. Hence there will be 6 x 168 meetings at the municipal level, 6 x 16 at the provincial level, that is 1,104 meetings in all. It is the job of the Candidacy Commissions to review every proposal. At the time of writing (5 January 2018), the mass organisations had held 970 of these meetings, at which12,640 people have been proposed as suitable to be National deputies. In addition, the Popular Councils (for details of Popular Councils see the article in the Autumn issue of CubaSí also make proposals to the relevant Municipal Candidacy Commission.

The Candidacy Commissions review all the proposals presented to them. Their first task is to see who has been proposed multiple times. For example, in the past, Fidel Castro would be proposed by many organisations across the island. Following de-de-duplication, people who have been proposed are interviewed to ensure that they are willing to stand in the election, and that they have the time to carry out the role. This will often depend on the type of work they do, and if their workplace can grant them sufficient time off work to carry out the role. It is important to note that most deputies continue with their normal employment, and carry out the duties as legislators in addition to their day jobs, receiving no payment for their work as National deputies.

Given the importance of the National Assembly, and the fact that there will be only one name on the ballot paper for each seat in the Assembly, it is important to ensure that people proposed are likely to be supported by the electors and that they have the relevant skills for the role. In order to establish this, the Candidacy Commissions carry out extensive consultation within neighbourhoods, workplaces, colleges and schools. Another role that falls to the Candidacy Commissions is that of ‘matching’ potential candidates to ‘constituencies’. This is necessary because of the way in which proposals are put forward. The meeting of the mass organisations which put forward suggestions for candidates are not limited to proposing people who live in their area. They are free to put forward anyone they think suitable. Consequently, there is a job to be done ‘matching’ potential candidates to ‘constituencies’.

When reviewing proposed candidates, the Candidacy Commissions must ensure that up to 50% of candidates are delegates which were elected to the municipal assemblies in November 2017. It is also the Commissions’ responsibility to ensure that the National Assembly reflects all sectors of Cuban society, including, workers from the state and non-state sectors, members of the mass organisations, farmers, nationally-known figures from the arts and sports, members of the armed forces, women, people of colour, all age-ranges, and from all parts of the island.

The Candidacy Commissions do not nominate the candidates; that role belongs to the municipal assemblies, who are ordinary citizens who were nominated and elected by their neighbours. Candidacy Commissions discuss their recommendations with each mass organisation at all levels to ensure that these meet with their approval. The Commissions then consult with all municipal delegates.

When this process is completed, the Candidacy Commissions provide the municipal assemblies the names of the people which, after their extensive consultation process, the Commission considers, would be best suited to the role of National Deputy on the basis of their skills and capacity, and, importantly, acceptability to the electorate. Municipal assemblies then formally nominate the candidates. Even at this late stage, municipal delegates can decline to nominate any candidate that the Candidacy Commissions have recommended, and the Commission must then present an alternative.

General Elections

After the formal nomination of candidates by the municipal delegates has been completed, elections can take place. Everyone over the age of sixteen has the right to vote, but voting is not compulsory.

On election day, each voter will vote for their representatives on their provincial assembly and for their representative to the National Assembly. Voters may vote for all, some or none of the candidates. Turn-out usually exceeds 90%. To be elected, candidates must receive at least 50% plus one of the total votes cast.

Electing the President of the Republic

Unlike the USA, Cuba does not elect its president directly. And unlike the UK, the head of state is not the preserve of a hereditary system. It is the National Assembly which elects the Head of State.

When the newly elected National Assembly meets on 19 April 2018, the first task of its 605 deputies will be to elect, from amongst its number, the officials of the Assembly (its president, vice-president and secretary). The President of the National Assembly is NOT President of the Republic of Cuba. The current incumbent is Esteban Lazo Hernández.

The Assembly deputies then elect the Council of State, which consists of a President and first vice-president, other vice-presidents, a secretary and 23 other members, totalling 31 members. This election is facilitated by the National Candidacy Commission, who meet with every deputy directly after they have been elected, and before the first session of the National Assembly.

Deputies have the right to propose any deputy to any of roles on the Council of State and also the president, vice-president and secretary of the Assembly. They write down, in secret, the post (President of the National Assembly, Ordinary member of the Council of State, President of the Republic etc) and the name of the deputy that they would like to see in that role. This is then deposited in a box anonymously, as in a secret ballot. The difference is, that it is up to the deputy who they propose for which post, the only restriction being that they must be an elected member of the National Assembly.

At the end of this process, when all deputies have made their proposals for the roles on the Council of State, and the three officials of the National assembly, the National Candidacy Commission tabulates all proposals and presents a list those who were most often suggested for each role, to the first session of the new National Assembly. The Assembly then votes to formally accept all those presented as nominees. Once nominated, the Assembly delegates elect the Council of State by secret ballot. The deputy who is elected president of the Council of State becomes the President of the Republic (Head of State), and also heads the Council of Ministers

In summary, Cuba’s general elections, held every five years, is a two-part process. It begins with communities nominating and electing their municipal delegates. There then follows the process of gathering thousands of proposals for the National Assembly deputies, with each of the 176 Candidacy Commission, each headed by trade union member, discussing, debating and consulting with tens of thousands of citizens, to find the most suitable candidates. This process takes three months or more. When this stage is complete, elections take place again, this time to elect the provincial assemblies and the National Assembly. The National Assembly then elects the President of the Republic.

Raúl Castro has publicly stated that he will not be accepting nomination for the position of President. The world’s press is rife with speculation about who will succeed him, and how this might change Cuba’s future policy. The same speculative noises were heard when Fidel announced, in February 2008, that he would not be accepting nomination to the Presidency due to illness, and again when he died in November 2016. This speculation reflects a view of the President as all-powerful, and does not take account of the collective decision-making of the Council of State, and ignores the role of the National Assembly. It also gives no credence to the involvement of millions of Cuban citizens in the extensive process of popular participation which takes place after the nomination and election of municipal delegates, and before the elections to the National Assembly. The strength of Cuba’s system lies in its participatory character, which ensures that its citizens regard their National Assembly, are truly representative of their society.

A recent comment on the Granma website from a member of the Cuban public sums up how most Cubans view their electoral system:

“The elections in Cuba are expression of participation of the people in the election and in the decision making. In Cuba democracy is real, it is to choose and more; it is to participate, decide, distribute and access fairly the assets our country has created.”

Lauren Collins is an expert on Cuba’s elections and has just finished a PhD on the country’s participatory democracy at the University of Nottingham.