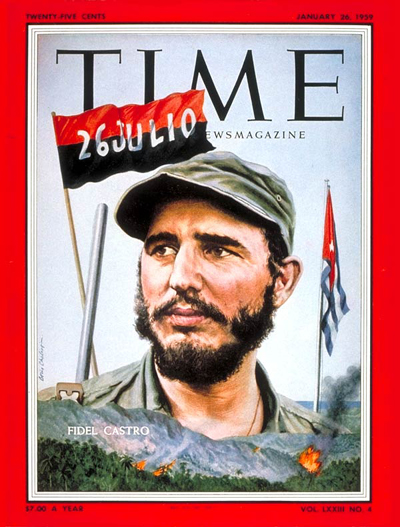

Fidel Castro – 90 revolutionary years

Summer 2016

The historic leader of the Cuban Revolution celebrates his 90th birthday on 13 August 2016, CSC executive member, Dr Francisco Dominguez looks back at his legacy and internationalism

"A great man is great not because his personal qualities give individual features to great historical events, but because he possesses qualities which make him most capable of serving the great social needs of his time, needs which arose as a result of general and particular causes.” GV Plekhanov

In the contemporary world nobody else symbolises the modern revolutionary spirit better than Fidel Castro. From his very first incursions into politics he seemed to have been imbued with an almost insane, verging on the irrational, faith in the victory of his undertakings, many of which were carried out against extraordinary odds.

It was with this spirit that he organised and led the military attack against the Moncada Barracks on the now historic date of of 26 July 1953 when he was not yet 27 years old.

The attack was a huge risk, involving 137 badly equipped, poorly trained fighters against one of the largest and best armed military garrisons in the country, housing more than 500 soldiers. Fidel’s insurgents faced far superior firepower and had a slim chance of success, but only if the surprise factor worked. It did not.

Following his capture after the attack, Fidel took the gamble to defend himself at the trial in a political context dominated by the intensely repressive Batista dictatorship.

In October 1960, Senator John Kennedy said: “Fulgencio Batista murdered 20,000 Cubans in 7 years - a greater proportion of the Cuban population than the proportion of Americans who died in both World Wars, and he turned democratic Cuba into a complete police state - destroying every individual liberty.” This gives a measure of Fidel’s audacity to undertake his own legal and political defence.

His closing defence speech, ‘History Will Absolve Me’, would make history as perhaps one of the most impressive political statements on why Cuba not only needed a revolution, but what the revolution’s intellectual, moral, historic, social and political foundations were. In it Fidel made the dictum that has informed his politics: “No weapon, no force is capable of defeating a people who have decided to fight for their rights.” Furthermore, in it we find the post-Batista programme of structural transformations to be implemented. It was a trait that was to inform his long political career: consistency between rhetoric, principles and practical action.

The Moncada adventure, and Fidel’s exceptional political performance at the trial, catapulted him to national prominence from which he drew the key political lesson of his politics: audacity, regardless of the odds. Hence, the training camp in Mexico; his apparently ill-advised naval expedition to Cuba in the Granma yacht with 89 fighters; the establishment of the guerrilla HQ in the Sierra Maestra with the 12 survivors of the disastrous Granma landing; and his unwavering conviction that Cuba was mature for Revolution. This continued all the way to the 1962 October Missile Crisis, when Fidel skilfully steered his country through one of the most dangerous moments in the twentieth century’s history. It was under his political and military leadership that Cuba inflicted the very first defeat of US imperialism in Latin America on 17 April 1961 at the Bay of Pigs. A battle he led as field commander from a tank in the theatre of war itself.

Fidel’s view of revolution is based on a Third World perspective of liberation against imperialism. Thus, Fidel’s internationalism was predicated on the need to build the broadest anti-imperialist unity in action in solidarity with the struggles of the peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America.

However, solidarity for Fidel went well beyond strongly worded statements and declarations of support, since he took it to unprecedented levels, which on many occasions involved the actual participation of tens of thousands of Cuban fighters in highly complex and dangerous areas. Fidel shared Che Guevara’s dictum that to “always be capable of feeling deeply any injustice committed against anyone, anywhere in the world”, was “the most beautiful quality of a revolutionary.”

The Cuban Revolution is also profoundly Latin Americanist, as espoused by Fidel in the very first pronouncements that defined the Revolution’s nature. Thus, in the ‘First Declaration of Havana’, he presents the Revolution as a continuum of the struggles of Bolivar, Hidalgo, Suarez, San Martin, O’Higgins, Sucre, Tiradentes and, of course, Cuban independence leader José Martí himself. But the people are key. Fidel poetically formulates this in the ‘Second Declaration of Havana’:

“…the dark-skinned, the poor, the indigenous, peasants, workers, women, have said enough and got on the march for their rights which have been suppressed for 500 years, and its inexorable march as a Giant will not stop until total success. This coming epic will be written by the masses, by the starving indigenous communities, landless peasants, exploited workers, mestizos, mulattoes, poor whites, our peoples in Latin America, those despised by imperialism, they will be the gravediggers of imperialist monopoly capital.”

US imperialism understood the highly emancipatory and contagious significance of the Cuban Revolution and thus has sought to crush it ever since 1 January 1959. This never led to any weakening of Fidel’s principles to the Cuban people, the Revolution or his internationalism. Under Fidel’s leadership Cuba not only developed the most sophisticated knowledge of Latin America as a whole, but it also strongly influenced the healthiest political currents in the region. Thus Fidel’s leadership and Cuba’s example were not just an inspiration of what a better world would be like, but also a spur to political action.

Fidel’s Latin Americanist conviction led him to give political support to Salvador Allende, even when the Chilean road seemed to squarely contradict, Cuba’s strategy of Revolution. He understood the deeply revolutionary nature of Allende’s government and visited Chile in 1971 and his words still resonate as strongly as at the time. He steered the revolution to also lend support to both the Nicaraguan and Grenadan revolutions thus eliciting the wrath of the US. The aggressive Reagan administration had both unleashed a horrific war of attrition against Nicaragua and ordered the US military to invade Grenada in the 1980s.

From the 1960s, consistent with the Revolution’s internationalism, Fidel gave Cuban support, usually soldiers and doctors, to revolutionary struggles in Africa including national liberation movements in Algeria, the Congo, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Angola, Ghana, Ethiopia, Central Africa, Eritrea.

After the collapse of Africa’s Portuguese empire, Fidel took the momentous decision to send thousands of Cuban volunteer troops to Angola, twice. Once in 1975, which decisively tilted the three-way anti-colonial struggle in favour of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola Party (MPLA), the left wing nationalist guerrilla movement, thus guaranteeing the country’s independence. Cuba’s 1975 intervention took place when apartheid South African troops were racing to crush the MPLA. By early 1976 Cuba’s contribution had helped both in pushing the South Africans out of Angola and in winning the war for the MPLA. One African newspaper wrote at the time “Black Africa is riding the crest of a wave generated by the Cuban success in Angola. Black Africa is tasting […] the possibility of realising the dream of total liberation.” Speaking at the United Nations, in response to US criticisms, Fidel said that Cuba was not guided by any materialistic concerns: “We are carrying out our international duty in helping the people of Angola.”

Then again in 1987. Fidel, at the request of the beleaguered MPLA government of Angola who were facing an all out military assault and invasion by tens of thousands of apartheid South African elite troops, took the extraordinary decision to send 50,000 troops. They defended Angola at the invasion of Cuito Cuanavale, in the country’s southeast. Fidel himself explained the significance of the undertaking:

“…the Cuban Revolution had put its own existence at stake, it risked a huge battle against one of the strongest powers located in the area of the Third World, against one of the richest powers, with significant industrial and technological development, armed to the teeth, at such a great distance from our small country and with our own resources, our own arms. We even ran the risk of weakening our defenses, and we did so. We used our ships and ours alone, and we used our equipment to change the relationship of forces, which made success possible in that battle. We put everything at stake in that action...”

The geopolitical impact of South Africa’s defeat was so huge that it would substantially contribute to the end of apartheid, the liberation of Mandela, and the independence of Namibia. No other non-African political leader has contributed more to the liberation of Africa from colonialism and imperialism than Fidel Castro, using the meager resources of a small but great Caribbean island. A scholar wrote with a great deal of justice: “Cuba is the only Third World nation with the foreign policy of a world power.”

The defeat of the Nicaraguan and Grenadan revolutions and the fall of the Berlin Wall, leading to the eventual disappearance of the socialist bloc and the collapse of the Soviet Union itself, left Cuba severely isolated and the Revolution faced extreme danger. The US sharply intensified the blockade seeking to strangle the island. Cuba’s Eastern bloc former allies turned nasty enemies. With the economy almost in a state of collapse, Fidel defended the socialist nature of the Revolution at whatever cost: “Cuban socialism was not constructed after the arrival of victorious Red Army divisions, our socialism was forged by Cubans in real struggles.”

Fidel’s unique ability to combine hard principles with a pragmatic nimbleness led Cuba to adopt the ‘Special Period’. Although this permitted small elements of capitalist entrepreneurship and joint ventures with foreign investment, it allowed Cuba to reinsert itself into the world economy, pretty much under its own conditions. It took the country out of the economic precipice in barely five years. The same nimbleness led Fidel to invite arch-reactionary Pope John Paul II to visit Cuba in 1998. The Pope took the opportunity to castigate Cubans for engaging in pre-marital sex and uttered a few generalities about liberty and democracy, however, Fidel scored a massive coup when John Paul II condemned both savage capitalism and the US blockade, committing US Catholics to actively campaign against the latter.

Fidel was the only political leader to realise Hugo Chávez’s political significance and invite the then presidential candidate to Cuba to engage in discussions and explore ways of collaborating with what at the time was a foggy thing called the Bolivarian Revolution. A young Hugo Chávez visited Havana and was warmly welcomed by the Comandante. It was there that he made one of his best formulations of the Bolivarian project. It was also the first sign that the three-decades-long neoliberal nightmare in the region was on the wane, that Cuba’s isolation was coming to an end, and that Fidel’s vision of a radical, united, independent and integrated Latin America could become a reality.

This was in 1994, four years before Chávez became Venezuela’s president and well before there was any inkling it would inaugurate the ‘Pink Wave’. Fidel’s vision and Cuba’s example, after half a century of resistance and adherence to socialist principles, had not only paid off, but the emulation of Cuba’s policies by the ‘Pink Wave’ governments ensured that tens of millions of hitherto impoverished and marginalised people began to experience the fruits of a better world. In his welcome to Chávez, Fidel combined rhetoric, eloquence, eulogy and rigour: “Chávez says he does not deserve the honours we are awarding him, but somebody who spent ten years (clandestinely) educating young Venezuelan military officers and soldiers in the Bolivarian ideas deserves these and many more honours.”

The United States 50-year-long aggression has been defeated by Fidel’s leadership on a large number of occasions. It began in 1960 with President Eisenhower’s attempt to humiliate the Cuban delegation to the UN by throwing them out of the Manhattan Shelburne Hotel. Fidel turned this into a sensational political victory by staying in Harlem’s Theresa Hotel and receiving a rapturous welcome by African-Americans. Ever since, Fidel has inflicted defeat after defeat to imperialism, not only by defending Cuba’s Revolution, but by also providing tangible material support to anti-imperialist struggles around the world. No wonder they hate him so much and little wonder that they have tried to assassinate him at least 638 times. US efforts to assassinate Fidel are the clearest manifestation of their utter failure to counteract, let alone defeat, the attractiveness of Cuba as a good example to imitate and emulate.

A scholar commenting on Fidel in a TV documentary was asked to sum him up in one phrase. He replied: ‘It is the year 2025, the US has finally lifted the blockade against Cuba, and Fidel has finally decided to die’. Or to put it another way, in Fidel Castro’s famous words: “Patria, socialismo o muerte!” (Homeland, socialism or death).

Happy Birthday Comandante!

Dr Francisco Dominguez is Head of the Latin American Studies Research Group, Middlesex University, London.