Honouring the life of Haydée Santamaría

Autumn 2022

Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt celebrates the life of revolutionary heroine Haydée Santamaría Cuadrado, whose birth centenary is 30 December 2022

Born on a small sugar plantation in central Cuba to parents of Spanish descent, Haydée (Yeyé to her close friends) moved to Havana in the early 1950s to live with her younger brother Abel. Together, they would help to establish the revolutionary movement that changed history.

The modest Vedado apartment of the Santamaría siblings became the home of resistance to the Batista dictatorship, with Haydée preparing food for insurgent students before joining them at the table to discuss strategy. It was there that an audacious plan was discussed to attack two of Batista’s main military barracks at Moncada and Bayamo.

Moving to a safe house in Santiago de Cuba in the summer of 1953, Haydée took a suitcase full of weapons with her and was helped off the train by one of Batista’s soldiers, who deposited her heavy luggage at the feet of her waiting comrades.

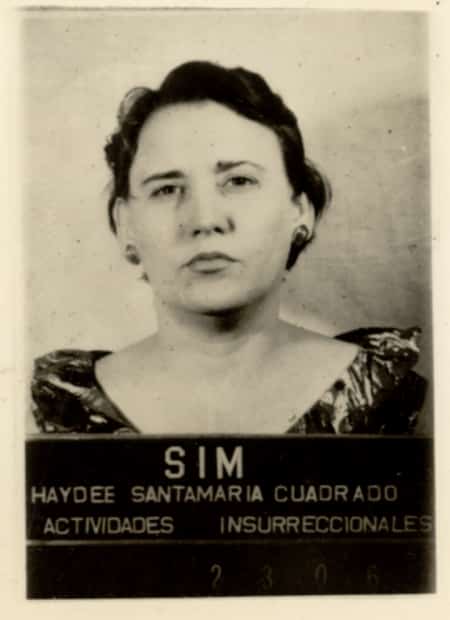

Together with Melba Hernández, Haydée was one of only two women among 160 men who took part in the 26 July attacks. She later recalled Moncada being the “worst, bloodiest, cruellest, most violent moment of our lives”. Among the dozens of combatants captured that day were her two “most intensely beloved human beings” – Abel and her fiancé Boris.

In the now-legendary speech Fidel Castro made during his subsequent trial, he paid homage to the two women who had fought alongside him:

“Frustrated by the valour of the men, they tried to break the spirit of our women. With a bleeding eye in their hands, a sergeant and several other men went to the cell where our comrades Melba Hernández and Haydée Santamaría were held. Addressing the latter, and showing her the eye, they said: ‘This eye belonged to your brother. If you will not tell us what he refused to say, we will tear out the other.’ She, who loved her valiant brother above all things, replied full of dignity: ‘If you tore out an eye and he did not speak, much less will I.’ Later they came back and burned their arms with lit cigarettes until at last, filled with spite, they told the young Haydée Santamaría: ‘You no longer have a fiancé because we have killed him too.’ But still imperturbable, she answered: ‘He is not dead, because to die for one’s country is to live forever.’ Never had the heroism and the dignity of Cuban womanhood reached such heights.”

Sentenced to seven months in prison for her part in Moncada, Haydée was later charged with deciphering and disseminating Fidel’s defence speech under the title ‘History Will Absolve Me’.

In 1956, Haydée helped to coordinate an uprising intended to distract the authorities from the arrival of 82 insurgents aboard the Granma. Using the nom de guerre of María, she played a vital part in the urban underground, honing her unique intuition for evading capture and death. She went wherever Fidel needed her to be, travelling to Miami to secure weapons from gangsters and returning to Cuba with bullets sewn into the folds of her skirt.

Having lost her love at Moncada, Haydée later married a young lawyer and fellow 26 July Movement member, Armando Hart Dávalos, who would become the first post-revolutionary minister of education and, later, culture. Together, they had two children and adopted many more, mainly young people displaced from their homes throughout Latin America.

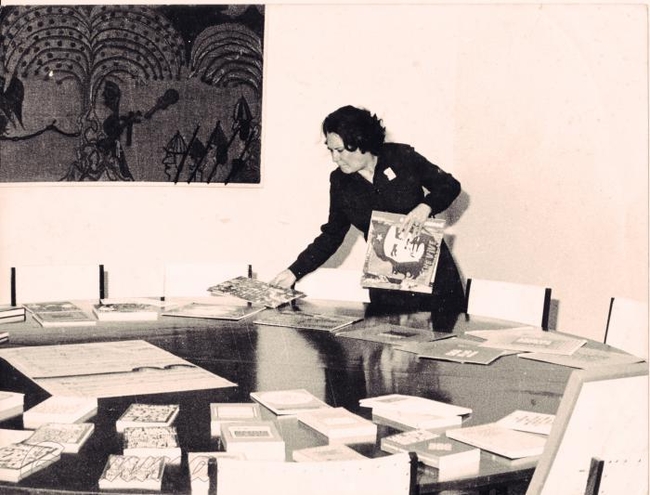

Turning down a position in the revolutionary hierarchy, Haydée’s greatest creation was an institution conceived to bypass the ideological blockade – the cultural house, Casa de las Américas. This quickly became – and remains – a nexus for intellectuals visiting the revolutionary heartland from the Americas and beyond, a place where experimentation is encouraged and solidarities are formed.

Haydée understood art as “the highest form of human expression and a necessary component of social change”. Becoming a member of the Central Committee of the governing Cuban Communist Party in 1965, she used her revolutionary prestige to nurture and protect a great many artists and writers within the walls of her cultural house, especially when policy temporarily took a dark turn in the first half of the 1970s. In this place, which still thrives in her image, creative intellectuals from around the world come together to play a part in the island’s ever-evolving social processes.

Within Cuba, it is written that, at the age of 57, Haydée’s “pain grew too much for her (the eternal pain her horrible executioners [sic] caused her after the Moncada attack), her mind grew darkened, and she took her own life”. Not only Moncada but a succession of tragedies compounded Haydée’s darker thoughts – the execution of her soul mate, Che Guevara; the loss of her dear friend and ally, Celia Sánchez, to cancer; the car accident that left her in permanent physical pain; the sudden and unexplained departure of her husband. The poet Margaret Randall, who knew Haydée, has posthumously diagnosed her as suffering from post-traumatic stress and concludes that “The question shouldn’t be ʻWhy did she kill herself?ʼ but ʻHow did she manage to live so fully for so long and give so much?’”

A heroine of the country

…Cover her with flowers, like Ophelia.

Those who loved her have been orphaned

Cover her with the tenderness of your tears.

Become dew to refresh your mourning.

And if the devotion of flowers is not enough

Tell her in her ear that it was all a dream.

Honour her as a brave woman

Who lost her last battle alone.

Do not remain long in her inconsolable hour

Her deeds are not destined to the oblivion of the grass.

Let them be gathered one by one,

There, where the light does not forget its warriors.

Extract from Cuban poet Fina García Marruz’s ode to Haydée Santamaría, written after her death.

Read: Haydée Santamaría: Rebel Lives

If you want to find out more about Haydée Santamaria’s remarkable and revolutionary life, this book tells her story in her own words based on interviews published in the 1970s and through the memories of her contemporaries, plus letters and poems dedicated to her.

CSC price £8.95 + £1.50 p&p

Haydee with Celia Sanchez

Arrest photo for participating in the Moncada attack

At the Casa de las Americas