Like the Last President to Visit Cuba, Obama Seeks a Change

New York Times | Monday, 22 February 2016 | Click here for original article

WASHINGTON — Imagine an American president in his final year in office, making a historic and carefully choreographed trip to Cuba to extend a hand of friendship to an island neighbour after decades of hostility and mistrust.

Long before President Obama had the idea, Calvin Coolidge made the journey to Cuba in 1928 — his only foreign trip as president — to address a conference of Western Hemisphere nations and declare “progress” and good will toward Cuba after a long period of strain. No sitting United States president has returned since.

Mr. Obama announced last week that he would end that streak with a visit next month, aiming to build momentum toward normalising relations with Havana before he leaves the White House. Along the way, he hopes to cement his legacy as the leader who broke with more than a half-century of rancor and estrangement and tried a new path of engagement with Cuba.

Mr. Obama’s planned trip bears faint echoes of Coolidge’s visit 88 years ago, with its message of change and a new chapter. In the intervening decades, the relationship between the United States and Cuba has grown only more complex and fraught with grievances, leaving Mr. Obama with a landscape that bears little resemblance to the one that greeted his predecessor in 1928.

Coolidge arrived by battleship in Havana’s harbour in January 1928. The dramatic entrance came with ceremonial guns booming, a flyover by military planes and an elaborate parade during which he was pelted with roses by tens of thousands of cheering Cubans assembled on streets, balconies and roofs. Cuba declared a national holiday for the occasion.

“It was the gayest and happiest welcome anyone ever received from this green island in the Caribbean,” The New York Times reported from Havana on Jan. 16, 1928. The display underscored American power at a time when the United States was a dominant force in Cuba, with the right to intervene in its internal affairs enshrined in a law known as the Platt Amendment, and was inserting itself aggressively in other parts of Latin America and the Caribbean, including Nicaragua and Haiti.

“The culture of U.S. paternalism prevailed at that time, and the Caribbean was basically a U.S. lake,” said Amity Shlaes, the author of the biography “Coolidge” and the chairwoman of his presidential foundation. The Americans, she said, expected the Cubans to welcome the president with a sense of “Dad is coming in his boat, and we love Dad.”

It is hardly the symbolism that Mr. Obama wants to project in March, when he will try to sweep aside decades’ worth of accumulated bitterness over American imperialism and meddling in Cuba and look to the future.

“Calvin Coolidge travelled there on a battleship,” Benjamin J. Rhodes, Mr. Obama’s deputy national security adviser, said last week, “so the optic will be quite different from the get-go here.”

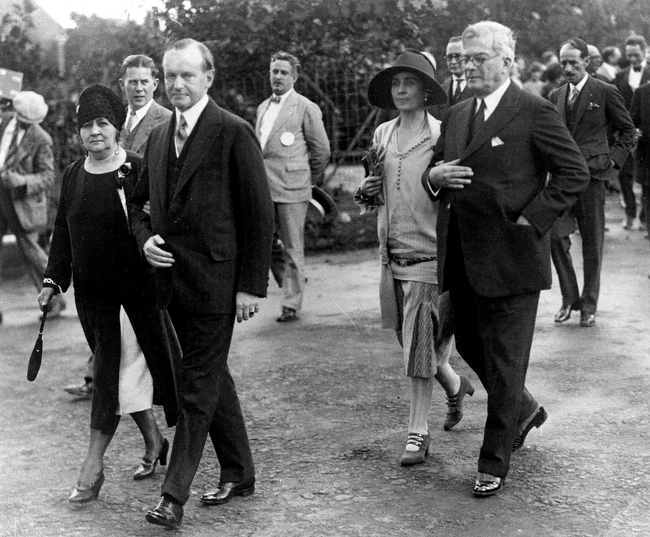

In 1928, Mr. Coolidge and his wife, Grace, boarded a train in Washington and rode for 40 hours to Key West, Fla., where they switched to the battleship Texas for the crossing to Havana, a trip that took two days. They were greeted at the port by Gerardo Machado, Cuba’s president, and his wife. The couple would host the Coolidges at the presidential palace in Havana and a country home nearby, feting them with two lavish banquets and accompanying them to a jai alai match and a sugar plantation.

Machado gave Coolidge a Panama hat, and there was much speculation about how the American president, whose country was in the midst of Prohibition, would navigate the etiquette challenge of being offered a drink of Cuban rum. (He simply turned his back and pretended to be talking to Machado when approached with a tray of daiquiris, one journalist recounted.)

News reports at the time indicated that Coolidge, known as Silent Cal for his taciturn demeanor, visibly enjoyed himself. To the Cubans, The Times reported, “he now is a smiling, and not a cold and silent, president.”

Mr. Obama and his wife, Michelle, will make the flight from Washington on Air Force One. The visual of the presidential limousine on the mostly frozen-in-time streets of Havana, crowded with 1950s-era cars, is likely to make for a striking contrast.

While the White House has not completed an itinerary, officials said Mr. Obama would meet with President Raùl Castro of Cuba — though not with his brother Fidel, the father of the 1959 Communist revolution and the embodiment of the enmity of the past — as well as political dissidents and entrepreneurs. Among the backdrops that Mr. Obama is said to be considering for a public speech to Cuban citizens is the capitol building in Havana, next door to the National Theatre, where Coolidge spoke.

Senators Ted Cruz of Texas and Marco Rubio of Florida, the two Republican presidential candidates of Cuban descent, have harshly criticised Mr. Obama for making the trip, arguing that he is rewarding a repressive regime that deserves to be shunned.

Coolidge’s trip was in part an attempt to defuse the anger of Latin American leaders about American policy in their region. In his address, he spoke of “an attitude of peace and good will” in the hemisphere, in which small nations are respected. “Today, Cuba is her own sovereign,” he said, calling the country “a complete demonstration of the progress we are making.”

But Coolidge did not use his visit to tackle the thorniest grievances souring the American relationship with Cuba. He made no mention of the Platt Amendment, which he was unwilling to modify despite Cuba’s entreaties, nor did he change his position on keeping the heavy tariffs the United States imposed on the island’s sugar, as Machado had asked him to.

“Coolidge’s speech was filled with empty rhetoric and did not forecast a real break with the past in terms of U.S. malevolent designs on Cuba and the rest of the region,” said Peter Kornbluh, an author of “Back Channel to Cuba,” which recounts the history of secret negotiations between the American and Cuban governments over 50 years.

“For Obama, this trip is really taking a serious stride toward cementing this policy change toward Cuba and consolidating his legacy of using engagement over isolation,” Mr. Kornbluh added.

Mr. Obama is expected to take several steps to further expand business and cultural ties with Cuba and repeat his call to lift the American trade embargo, noting that only Congress can do so. (Coolidge, too, had deferred to Congress on whether to lift the sugar duties.)

Coolidge also saw his trip as a new beginning with Cuba. Thirty years before, Theodore Roosevelt had traveled there to challenge Spain’s colonisation of the island, and charged up San Juan Hill. Victory in the Spanish-American War ushered in a period of United States control.

“Teddy Roosevelt went to Cuba to make war; Coolidge went there on a diplomatic mission,” Ms. Shlaes said. “He felt that he was there symbolically, as a ceremonial bringer of good will.”

Mr. Obama is gambling that his own journey will herald a more lasting sea change in the United States relationship with Cuba than Coolidge’s did. Five years after that visit in 1928, Machado was overthrown in a revolution — with American backing.