The U.S. is pushing Latin American allies to send their Cuban doctors packing — and several have

Washington Post | Friday, 24 January 2020 | Click here for original article

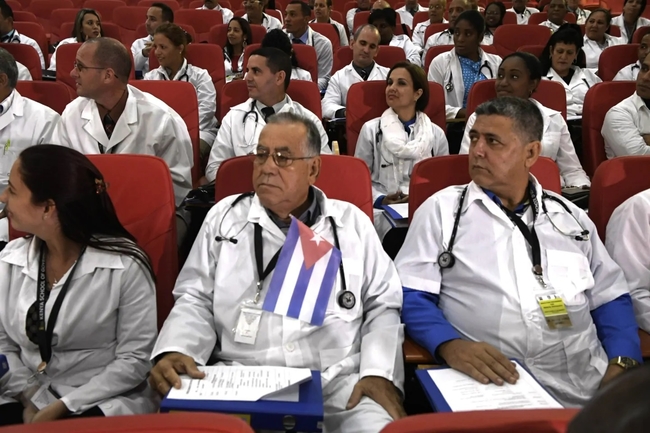

From the earliest days of the revolution, Cuba has been sending doctors to treat the poor people of the developing world — a key source of income and influence for the communist island long isolated by a U.S. embargo.

Now the Trump administration is targeting the government’s signature medical brigades, urging U.S. allies to cancel their health cooperation agreements and send their Cuban doctors packing.

At least four Latin American countries have done so — another blow to the island as it struggles under tightening U.S. sanctions.

“The U.S. government’s crusade against Cuba’s international medical cooperation is an insult,” Cuban Foreign Minister Bruno Rodríguez tweeted in December. Officials said the program had provided hundreds of thousands of surgeries and training sessions to the countries that canceled, and called the U.S. effort “a disgraceful and criminal act against peoples in need of medical assistance.”

AD

As sanctions bite in Cuba, the U.S. — once a driver of hope — is now a source of pain

The program, which has sent 400,000 doctors to 164 countries since 1960, has always been controversial. Host governments pay the Cuban government; doctors have said they are paid little and must leave their families behind in Cuba so they don’t defect.

But medical diplomacy has helped Cuba gain votes in the United Nations from beneficiaries in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa and the Middle East, and it has been a large source of government revenue: $6.3 billion in 2018, more than 6 percent of reported gross domestic product.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has called the program a form of slavery and human trafficking.

“We urge host countries to end contractual agreements with the Castro regime that facilitate the #humanrights abuses occurring in these programs,” Pompeo tweeted this month. The U.S. government imposed visa restrictions on officials involved in the program, and the Senate has approved resolutions to consider reinstating a parole program that encouraged the doctors to defect.

AD

The U.N. Human Rights Council’s rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery made an official inquiry to the Cuban government in November. Cuba responded that the program was “committed to the principles of altruism, humanism, and international solidarity, which have guided it for more than 55 years,” and said allegations that doctors are forced to participate are “absolutely false.”

“It’s unacceptable to mix Cuba’s medical collaboration with the horrid crime of human trafficking, modern slavery or forced labor,” the government said in a statement posted on the council’s website. “It’s also unacceptable that the Human Rights Commission is being used to promote false campaigns led by the United States against the humane work that has been developed by Cuba’s international medical cooperation.”

The recent cancellations reflect a broader change across Latin America — a conservative backlash to the pink tide of leftist governments of the early 21st century, now receding, that has increased Cuba’s isolation.

AD

Cubans were once privileged migrants to the United States. Now they’re stuck at the border, like everyone else.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro canceled a $200 million annual agreement in late 2018, ousting more than 8,000 doctors in a program that had served the rural poor since 2013, after objecting to paying the Cuban government.

Ecuadoran President Lenín Moreno sent 400 doctors home in November, in the midst of protests against austerity, and suggested that some of them might have been inciting violence.

Cuba recalled 700 doctors from Bolivia after the resignation of socialist President Evo Morales in November. Cuban officials said the doctors were vulnerable to attack after the interim government of Jeanine Áñez suggested that they had been paid by Venezuela to foment unrest.

And Cuba canceled the program in El Salvador in April, after accusations that doctors were performing surgeries without legal authorization.

“The backlash is an important blow for Cuba’s dual purpose of income and influence,” said Maria Welau, executive director of the Cuba Archive. “The Cubans are losing both in Latin America.”

Cuba has suffered amid tightening U.S. sanctions under President Trump, after an Obama-era thaw, and a declining flow of subsidized oil from its ally Venezuela. President Miguel Díaz-Canel has struggled to find a balance between continuing the communist legacy of Fidel and Raúl Castro and opening the island to economic modernisation.

At least 18,000 Cuban doctors continue to work in more than 60 countries, including at least 15 in Latin America. John Kirk, the author of “Healthcare Without Borders: Understanding Cuban Medical Internationalism,” says the program has saved lives throughout the developing world.

As Venezuela’s misery grows, U.S. focus shifts to Cuba’s role

Cuban doctors have been deployed to fight diseases such as Ebola in West Africa and to treat the victims of natural disasters — they were the first on the scene after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti.

Kirk, a professor of Latin American studies at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, said Cuba is likely to find other countries to take the doctors who have been kicked out of or recalled from its Latin American neighbors.

“Cuba has more doctors working in the developing world than all of the G-7 countries combined,” Kirk said. “Those calling Cuban doctors to defect and countries to end cooperation miss the point, which is that thousands of poor people have greatly benefited from it and would be negatively impacted without it.”