Cuba's post-revolution architecture offers a blueprint for how to build more with less

The Conversation | Friday, 19 November 2021 | Click here for original article

Around the world, there’s a conjoined crisis of climate change and housing shortages – two topics at the top of the list of discussions in the recent COP26 climate summit in Glasgow.

Construction and buildings account for more than one-quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions. Meanwhile, according to a September report by Realtor.com, the U.S. alone is short 5.24 million homes.

Addressing both crises will require building structures more sustainably and more efficiently.

But this isn’t the first time architects and governments have had to deal with dwindling resources and the task of housing large numbers of people. In 1959, an armed revolt led by Fidel Castro ousted Cuba’s military dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista. As part of a broader plan to improve the quality of life for millions of Cubans, Castro’s new government sought to develop a program to mass-produce new housing, schools and factories.

In the years that followed, however, this dream clashed with difficult realities. Sanctions and supply chain disruptions had created a shortage of conventional building materials.

Architects realized they needed to do more with less and invent new construction methods using local materials.

A thousand-year-old technique

In an article that I co-authored with architect and engineer Michael Ramage and architect Dania González Couret, we explored the creative challenges of this period by focusing on a specific structural element that these Cuban architects soon seized upon: the tile vault.

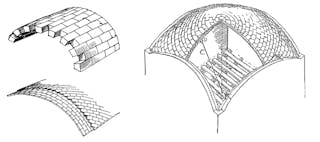

Tile vaulting is a technique that flourished in the eastern Mediterranean after the 10th century.

It involves constructing arched ceilings made of multiple layers of lightweight terra cotta tiles. To build the first layer, the builders use fast-setting mortar to glue the tiles together with barely any temporary support. Afterward, the builder adds more layers with normal cement or lime mortar. This technique doesn’t require expensive machinery or use of a lot of timber for formwork. But speed and craftsmanship are paramount.

Because of its affordability and durability, tile vaulting spread to different parts of Europe and the Americas. It became known as Guastavino tiling in the U.S – a nod to Spanish architect Rafael Guastavino, who used the technique in over 1,000 projects in the U.S., including the Boston Public Library and New York’s Grand Central Station.

Vaults in vogue

In Cuba, tile vaults were famously used to build the National Art Schools, or Escuelas Nacionales de Arte.

Fidel Castro advocated for the construction of the five schools on what, before the revolution, had been a golf course in Cubanacán, a town west of Havana.

Designed by Ricardo Porro, Vittorio Garatti and Roberto Gottardi, the schools integrate terra cotta shells and arches with the site’s green landscape. They were long thought to be the only tile vault buildings in post-revolution Cuba.

However, we discovered that the National Art Schools are only the tip of the iceberg. From 1960 to 1965, a range of vault experiments and projects took place across the country.

Shortly after the revolution, architects and engineers at the Ministry of Construction – known as MICONS – went to Camagüey, a province known for its terra cotta brick-making, to learn more about the craft. One of these architects, Juan Campos Almanza, then a recent graduate of the University of Havana, led the research team. As an experiment, he built a load-bearing vault on the grounds of the Azorin brick factory.

It was a success. He went on to use the design to construct affordable and elegant beachfront homes in Santa Lucía, north of Camagüey, using the same vault design.

The best of both worlds

Brick-and-tile vault construction appeared to be a promising solution to build replicable and cost-effective ceilings.

The Center of Technical Investigations, an agency tasked with developing housing, schools and factories, used Almanza’s research to construct its own vaulted offices. An outdoor space nearby – famously called “El Patio del MICONS” – became a staging ground for more structural experiments.

In El Patio, craftspeople, engineers and architects worked together to develop affordable vaulted buildings, while teachers at El Patio’s tile masons’ school taught building techniques to cohorts of apprentices.

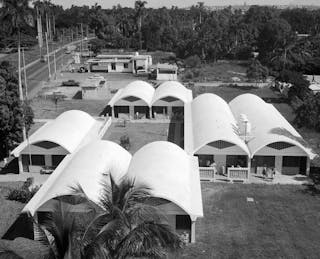

Vaulted buildings and homes soon started cropping up across the country. In 1961, Juan Campos Almanza completed his first housing projects in Altahabana, a new neighborhood located near Havana, building simple barrel vaults on prefabricated beams. Similar designs were used for more beachfront houses, schools and factories.

In his report about the Altahabana pilot project, Campos defined his method as “tradicional mejorado,” or “improved traditional construction” – a mix of conventional building methods with some prefabricated elements.

This way, he argued, builders could gain the best of both worlds: The construction, some of it built by hand, was fast and replicable. And it didn’t require a lot of materials and preexisting infrastructure.

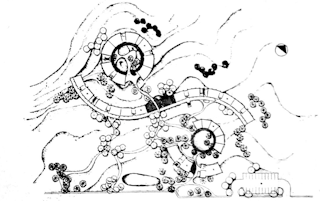

The best example of this construction method is the vaulted Pre-University Center at Liberty City, the site of a former U.S. Army base. The structure was designed in 1961 by Josefina Rebellón, who at the time was a third-year architecture student.

Only a couple of miles from the Schools of Art, Rebellón’s design was completed in 18 months. It was made up of two circular vaulted buildings, with conical vaults and prefabricated beams, with an undulating two-story classroom building between the two circles.

A brief experiment with a lasting legacy

These exciting new construction methods didn’t last long.

In 1963, Havana hosted the conference for the International Union of Architects. That year’s theme was Architecture in Developing Countries.

The conference gave Cuban architects an opportunity to reflect on their recent experiences. The Ministry of Construction pushed to end what it viewed as a period of experimentation; mass housing, they argued, demanded industrialized construction.

Buildings started being made in factories and then assembled on site. Skilled and specialized labor, like vault-building, was no longer seen as an asset but an obstacle, since vault builders were difficult to find in the country’s remote areas, and novice builders required extensive training.

Yet the story of these buildings offers lessons for designing with scarcity.

The ability to experiment is important. Coordination among builders, governments and architects is crucial. And craftsmanship matters, too, whether it’s tile vaulting or traditional carpentry.

For too long, buildings that required craftsmanship have been thought of as overly expensive pet projects that deployed techniques better suited for a different era. But the Cubans were able to show that craftsmanship can be developed, scaled up and combined with technological advances.

Today, a handful of promising initiatives show how the craft of tile vaulting can serve for the low-carbon construction of buildings or engineered ceiling systems. Back in Cuba, tile vaulting is now being taught in the Escuela Taller Gaspar Melchor, a training center in Havana’s historical center.

Cuba’s vaulted architecture reflects the relationship between necessity and invention, a process that many people mistakenly think of as automatic. It isn’t. It is a relationship based on perseverance, trial and error and, above all, passion.

Look no further than what Juan Campos Almanza and his peers left behind on the island: beautiful, replicable buildings, many of which are still standing today.