Love is the Law: Cubans vote yes to new progressive Family Code

News from Cuba | Monday, 26 September 2022

On 26 September 2022 the Cuban people voted to adopt what has been described by many as the most progressive Family Code in the world. In a national referendum, 66.87% of voters approved legislation which includes the right to marriage, adoption and assisted reproduction for same-sex couples, and redefines what it means to be a family, putting an emphasis on love, human dignity, equality and non-discrimination.

The referendum came after a six-month period of consultation which saw 79,000 neighbourhood meetings, generated 434,000 comments and proposals, and resulted in 49.15 per cent of the original draft being modified in response to public feedback. The draft presented in the referendum was the 25th version of the document, which had been revised by experts and specialist commissions before receiving final approval by the National Assembly.

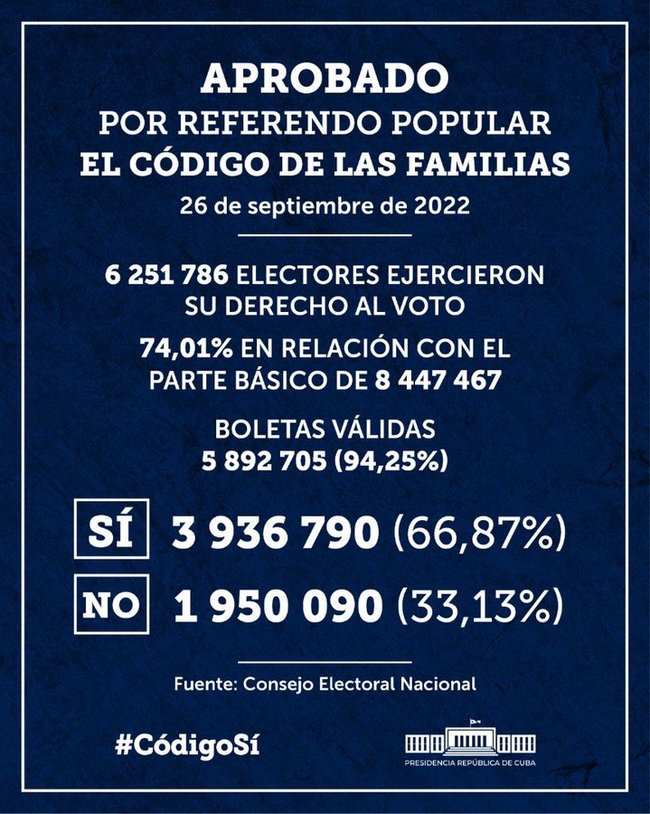

Turn-out for the final vote on 26 September was 74.01 per cent (6,251,786 people) out of a total potential electorate of 8,447,467. Of the 5,892,705 (94.25 per cent) of valid votes cast, 66.87 per cent voted yes, and 33.13 per cent no.

The new code also enshrines rights for the vulnerable in society including the elderly, children, adolescents and people with disabilities as well as enshrining womenʼs reproductive rights over their own bodies. Parents will now have ‘responsibility’ for, rather than ‘custody’ over children; corporal punishment will be illegal; and young adults will enjoy more freedoms. The Code enshrines domestic violence penalties and expands the working rights of full-time carers, as well as recognising that there should be an equitable distribution of domestic work.

It comes after years of work by activists in Cuba, including lobbying and educating by Cubaʼs Centre for Sexual Education (CENESEX) and the Federation of Cuban Women (FMC).

Cuba’s President Miguel Díaz-Canel had called publicly for a yes vote. Speaking to reporters on the day of the vote, he called on Cubans to “look at it with our hearts and also vote for it with our hearts, it will be voting for Cuba”.

As well as a campaign from conservative religious groups and churches, some opposition groups had been calling for people to vote no as a protest vote against the government and the economic situation. Rafael Hernández, editor of the Cuban magazine Temas, commented that “politicising the code is a way of trying to further polarise the national situation.”

Acknowledging the opposition campaign, the Cuban president said: “We have to get used to the fact that on such complex issues, where there is a diversity of criteria... there may be people who vote to punish (the government),” and that “that is also legitimate.”

Díaz-Canel said he was hopeful of a yes vote, but “regardless of whether ʻyesʼ or ʻnoʼ wins... the popular debate that has been generated has contributed to our society.”

You can read more about the content, history and opposition faced by the Family Code in the excellent article by Cuban journalist Beatriz Ramírez López below.

Cuba’s Family Code: Until Love is Law

What changes with Cuba’s new Family Code?

For children and teenagers, grandparents, people with disabilities and people in vulnerable conditions, people who have been discriminated against, men and women alike, groups of people who have been historically rendered invisible… This is a Code that does not exclude them. A Code of rights and love.

On 25 September, Cuba voted to ratify a new Family Code, based on plurality, affection, and social justice.

The country’s 2019 Constitution had already introduced a number of principles that responded to the evolution, development, and changes experienced by Cuban families. The family structure, established as the fundamental body of society, was, from that moment on, no longer conceived according to the traditional and patriarchal model.

Cuba’s Magna Carta not only set forth the principles of family diversity, but it also established the idea of equality among all people, regardless of race, gender, sexual orientation, or gender identity. Thus, this declaration legally acknowledges the same rights and freedoms.

Between February and April this year, Popular Consultation processes were conducted across the country to discuss the Family Code draft. In the discussion spaces, the early draft was edited and adjusted according to the perceptions and needs of the Cuban population. According to the country’s National Electoral Council, more than 61 percent of participants said they approve the Code.

This new legislation, which will replace the current Family Code that has been in force since 1975, sets forth a very different concept of family from the religious and sexist standards imposed in the past. It also establishes the paradigm of environments free from violence, respectful and affectionate child-rearing, and a country where all rights for all people are paramount.

A Code for All Families

The structure of the bill that was put to the referendum includes eleven titles, 474 articles, 5 transitional provisions, and 44 final provisions.

Militants, feminists, LGBTQ+ people, and other collectives feel that this Code is a dream that has been enshrined over the course of many years of struggle. A dream that is put on top of a political will to create an inclusive society, with all the nuances and diversity of human beings.

One of its most revolutionary topics – which has been discussed at length in a state that is grounded in a strong base of Catholic and Protestant churches and deep-rooted patriarchy – is the acknowledgment of the legal union between people of the same gender and their right to adopt.

The protection of the most vulnerable segments of society, including older adults, people with disabilities, and people in vulnerable conditions, is included in the substantive text of the Family Code. It acknowledges their rights and sets forth guarantees to enforce these rights.

The new Code also establishes the defense of older adults and their role at home as important and active people, acknowledging their contribution in caring for and protecting babies. Consequently, grandparents are granted the right to raise their grandchildren in cases of parental abandonment or any other reason. It also sets forth the right to self-determination and equal opportunities in the family environment.

Child care and protection has been a key point in the discussion. First of all, the expression “power of the father” [“patria potestad”] is replaced with “system of parent responsibility,” focusing on child-rearing not as an exercise of possession and violence, but rather as a process based on respect, conversation, and kindness. Moreover, children and teenagers are considered rights-bearing individuals, having their ideas and thoughts respected in a manner consonant with their progressive autonomy.

New regulations were created regarding filiation. The current rules include relationships established by blood or adoption, and they will now be expanded to include same-sex couples, introducing the social-affectionate parentage and the acknowledgment of assisted reproductive technologies.

Cuba’s new Family Code is a necessity. As a country, we have a long-standing debt with certain groups of the population, and we need regulations, strategies, and legal mechanisms that are in accord with the current times.

Challenges to Cuban Families

In this era of disinformation, introducing new legal terms has been challenging, due to media manipulation and a highly sexist culture that resists the multiple forms of family structures.

In this sense, religious fundamentalists have created campaigns to support the “original family” and several other campaigns that twist the meaning of parent responsibility and education from a gender perspective.

One of the strategies promoted by religious leaders has been to spread fear about the alleged “homosexualisation” and sexualisation through education and separation of parents and children when the government sees fit.

Ultraconservative sectors in Cuba are currently dedicated to a highly sexist education, full of gender stereotypes, as well as to exercising child-rearing through imposition.

But their conversation has not been exclusively about the control and manipulation of children. They also question the rights Cuba women have secured decades ago, such as the access to work and abortion. Similarly, they have been reiterating ideas about submissive wives, whose social and divine mission should be exclusively focused on caring for their family and bearing children.

In addition to the homophobia, transphobia, and misogyny that characterize these sectors, the progressive communities of the island also face a number of prejudices and stereotypes that are part of the collective imaginary. The radical right has been using the popular vote as a political weapon, carrying out numerous manipulative campaigns against rights on social media.

The patriarchal structures cemented in society seemed virtually impossible to change. But while raising awareness to end the practices we have rendered natural for decades requires a long-term process, having legislation that acknowledges gender-based violence, women’s double shift, and the primary role of caregivers while condemning all expressions of intrafamily violence in all its manifestations – that is a truly revolutionary step.

This is because the Family Code bill in Cuba demonstrates how necessary it is to have an equitable division of domestic work, as this load has been historically shouldered by women. It acknowledges Cuban women’s right to improve themselves without being overloaded at home, while setting forth for the first time the protection of caregivers and the pursuit of happiness.

Amid this scenario, the struggle for diversity, the respect for women’s sexual and reproductive rights, the end of all manifestations of discrimination, and the condemnation of all kinds of family violence is now more than ever a battle we must win.

Beatriz Ramírez trained in journalism at Havana University and at the Women’s Publishing House [Editorial de la Mujer]. This article appears on the website capiremov.org