New relationship is a greater challenge to Obama than to Havana

Blanche Petrich, Progresso Weekly | Wednesday, 19 August 2015 | Click here for original article

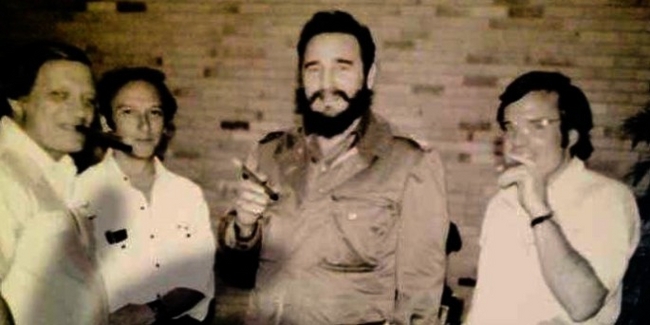

Frank Mankiewicz, Saul Landau, Fidel Castro and Kirby Jones meeting in Havana in 1975

During the five decades of confrontation between the United States and Cuba, there were periods of top-secret contacts and meetings, periods ruled by an absolute freeze, and times when the threats of the hemispheric power rose and even became violent.

There were moments so critical that Gen. Alexander Haig, a notable “hawk” in the administration of President Ronald Reagan, once warned the Soviet ambassador in Washington [Anatoly F. Dobrynin] and Mexican Foreign Minister Jorge Castañeda de la Rosa that the Pentagon might decide to bomb the island.

At another juncture, Haig himself acknowledged that a dialogue with Fidel Castro was indispensable for Washington and in 1982 traveled to Mexico City to meet with Cuban Vice President Carlos Rafael Rodríguez. Pragmatism or realpolitik was assumed by both administrations. Much of that history is still untold.

Diplomat Ramón Sánchez-Parodi, who headed the Cuban Interests Section in Washington from Sept. 1, 1977 to April 30, 1989, realizes that, in the face of the new reality, with full relations established between the old rivals, “we Cubans should tell our version of history.”

And they also should raise their demands to the United States, among them the most heartfelt: the lifting of the blockade.

Former Vice Minister of Foreign Relations, member of the Council of State and founder of the Communist Party of Cuba, Sánchez-Parodi views the outlook for the historic process just beginning as a challenge greater for the government of Barack Obama than for the government of Raúl Castro.

“They are the ones who must dismantle the state of affairs they have created,” he says. “We did not blockade them or sanctioned them or financed their internal subversion. How can they maintain the blockade and pretend that they’re normalizing the relationship? I cannot imagine.”

BLANCHE PETRICH: They maintain that the decision does not depend on Obama but on the U.S. Congress.

SÁNCHEZ-PARODI: “Yes, it depends on the legislative. During 12 administrations they have maintained it with laws, regulations, initiatives, rules.”

B.P.: What if Hillary Clinton doesn’t win the election?

S.P.: “Marco Rubio or Ted Cruz might win, but that doesn’t alter history. It is not a question of persons but of a world reality that’s dictating the conditions for this process.”

At the time of my interview with the author of the book “Cuba-USA: A 10-time Relationship,” the magazine Mother Jones has published details of the latest scheme leading to the reopening of the two embassies, with episodes and actors that not even Secretary of State John Kerry knew about.

The revelations of Peter Kornbluh and Michael LeoGrande [in their book “Back Channel to Cuba”] do not mention who were the Cuban protagonists in this delicate operation that began 18 months before the surprising unveiling of the story, on Dec. 17, 2014.

It was Sánchez-Parodi’s task to establish contact with the administrations of Richard Nixon, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and the George H. W. Bush administration in its early days.

B.P.: Who took the first steps? Carter?

S.P.: “No, that began earlier, in June 1975. Contacts always existed, but officially we were forbidden to talk to each other. It was Henry Kissinger, under Nixon, who made the first move.

“Frank Mankiewicz and Saul Landau, progressive U.S. academicians (both now deceased), conveyed to the State Department their interest in traveling to Havana. And Kissinger took advantage of this to send an unsigned letter to Fidel Castro, proposing a conversation.

“What Kissinger proposed was based on recognizing the substantive differences between the two governments while pointing out that they were no reason to maintain a perpetual hostility. The Cuban government analyzed the proposal and responded positively.

“Then came time to name representatives: me, for the Cuban side, and Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger. We held a first secret meeting at New York’s La Guardia Airport in January [1976.] There, we spoke only about the operative aspects. Later, in July, another meeting at the Hotel Pierre [in New York City], which lasted three or four hours.

“The central issue was the blockade. The United States did not oppose lifting it. What’s more, it was interested, but was unable to lift it because the Organization of American States had imposed collective sanctions against Cuba precisely at the urging of Washington.

“If the U.S. lifted the sanctions unilaterally, it would be contravening an O.A.S. resolution that said that no member country could maintain relations with us.

“It was a dilemma that had been discussed at the O.A.S. since 1973, without finding a solution to the trap that they themselves had set. Eagleburger told us that if the O.A.S. nations proposed a lifting of the embargo, the U.S. would not oppose it. We left the table with the idea of meeting again in two months. That never happened.

“The meeting was repeatedly postponed until, to our surprise, the dialogue broke up for the most trivial reason: Cuba’s support for Puerto Rican independence.

“Nixon fell because of the Watergate scandal and President Gerald Ford came to the White House eager to be elected in the 1976 election. To please the right, he used the pretext of Cuba’s support for the Angolan independence movement.”

B.P.: Was it a pretext?

S.P.: “Yes, our military presence in Africa was still minimal. Ford agreed with Kissinger that the negotiation with Cuba would not be made public until after the elections, but then continued the impasse because of the Angola issue.

“However, two years later, with Cuba much more involved in the Angolans’ resistance against the UNITA guerrillas and the South African incursions, Carter ordered a resumption of the contacts.

“In 1977, [the Americans] made the negotiation official and public and proposed that the two governments open our interests sections. As facilitators, we chose Czechoslovakia and they chose Switzerland.”

B.P.: Is that the usual procedure when two countries don’t have diplomatic relations?

S.P.: “The way we set up the arrangement — with the authority to carry out almost all the functions conducted by a normal mission, almost like an embassy without name or flag — no, it’s not usual. The idea was to be able to take the next step, full reestablishment, almost immediately. But it took 30 years to make it a reality.”

B.P.: Did Carter stop it?

S.P.: “He was caught between two streams: the conservative one, held by his national security adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, and the liberal one, held by his Secretary of State, Cyrus Vance.

“Even back then, there was discussion about the issues that today are brought back to the table, for instance, mutual indemnification. They acknowledged our claim, made in the 1970s, and we acknowledged theirs. It was up to me to convey to them our position. The problem lies in the amounts.”

Sánchez-Parodi explains that the Cuban Interests Section offered to indemnify private owners whose goods and capital were expropriated by the revolutionary government. But Washington recommended to the owners that they shouldn’t accept but should file their claims so the authorities could collect the money. The claimants would receive tax breaks.

“As to our demand, we have made our calculations on the basis of the damages caused by the blockade, the terrorist accounts and the bank accounts that were expropriated by the United States. What’s important here is that the two governments admit their debts and speak out publicly.”

The Reagan era: Two extremes

B.P.: As chief of the Cuban Section, did you maintain a dialogue with the U.S. authorities?

S.P.: “Always. With the Department of Defense, the CIA, the FBI, the departments of Commerce and the Treasury. Hostilities increased under Ronald Reagan but it was always evident that [the Americans] didn’t want to give up a direct communication with us. They never wanted to eliminate the mechanism of interest sections. We continued to negotiate the memorandum of understanding.”

It is surprising that Sánchez-Parodi stresses this continuous line of discreet contacts between Cuba and Washington at a time when antagonism was brutal, worldwide. Those were the years of U.S. military intervention in Nicaragua and El Salvador under the excuse of Soviet and Cuban interference, the years of the invasion of Grenada and the assassination of its prime minister, George Bishop.

“True,” says the Cuban diplomat, who later became vice minister of Foreign Relations and ambassador to Brazil, “but they were also the years of the South African accords, perhaps the last relevant act of Reagan’s diplomacy in December 1988.

“Cuba was present in Angola from 1975 to 1989 and Washington understood that a dialogue with us was indispensable. Its support for the genocidal forces of UNITA’s Jonas Savimbi and the apartheid regime in South Africa had alienated [the U.S.] from the other African nations and the socialist camp and gave it a very bad image worldwide.

“Very little is said of the South African accords, yet they wouldn’t have been possible without Cuba. What would have happened there? Today, there is stability in Angola, Namibia is independent, and South Africa has no apartheid.”

During each U.S. administration, there were highs and lows in the confidential communication with Cuba. Sánchez-Parodi recalls the time when Mexico, Colombia and Venezuela asked Bush Sr. to take executive action to lift the blockade. That proposal foundered after the 1992 elections.

Bill Clinton signed the Torricelli and Helms-Burton laws that tightened the political and commercial siege of the island, just when Cuba’s allies in the socialist bloc collapsed.

That was also the era of the terrorist provocations, the illegal overflights by the anti-Castro group Brothers to the Rescue, and the downing of two of their planes.

Unlike the advances and retreats of the past, the thaw today cannot be reversed, Sánchez-Parodi believes. And this time it is up to the two sides. We all have to change a mental attitude that conditioned us for half a century.