Operación Carlota: 50 Years of Cuba and African Liberation by Isaac Saney*

News from Cuba | Tuesday, 4 November 2025

"The Cuban people hold a special place in the hearts of the people of Africa. The Cuban internationalists have made a contribution to African independence, freedom and justice unparalleled for its principled and selfless character.” Nelson Mandela, July 26, 1991

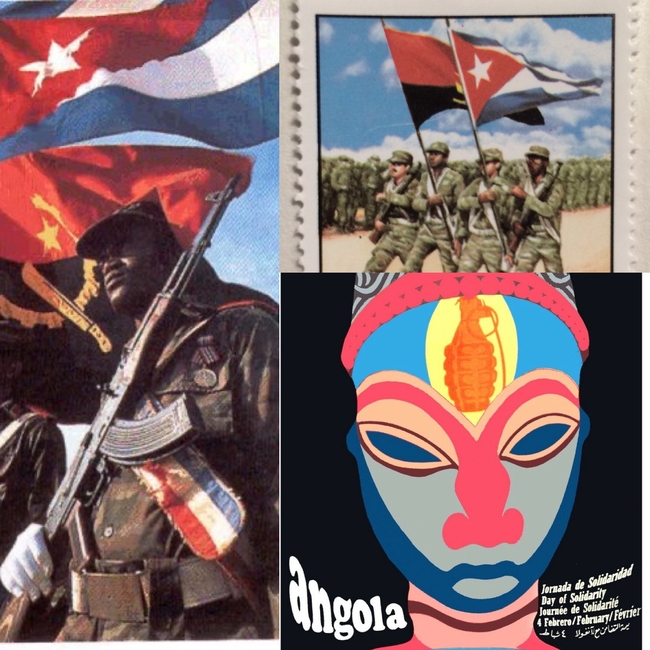

November 5 2025 marks the 50th anniversary of Operación Carlota, Cuba's internationalist mission in southern Africa, which was pivotal in securing Angola and Namibia’s independence and hastening the fall of apartheid South Africa. The 50th anniversary of Operación Carlota marks a milestone in the global struggle against colonialism, apartheid, and imperialism. The successful military defense of Angola by Cuban and Angolan forces hastened the independence of Namibia in 1990 and dealt a severe blow to the apartheid regime in South Africa, hastening its demise.

On 5 November 1975, in response to a direct and urgent appeal from the newly independent government of Angola, Cuba launched Operación Carlota. This bold act of internationalist solidarity was in direct response to a military invasion by apartheid South Africa, which, backed by the United States and other Western powers, sought to crush Angola’s fledgling Black-led government and halt the broader tide of African liberation. Angola had only just emerged from a protracted and brutal anti-colonial war against Portuguese colonialism. Its independence, won through great sacrifice, was immediately threatened by a foreign-backed effort to impose a client regime and derail genuine sovereignty.

In this context, Operación Carlota—named after Carlota Lucumí, an enslaved African woman who led a revolt in Cuba on 5 November 1843—was a decisive intervention. Cuban forces, in coordination with Angolan troops, halted the South African advance toward Luanda and drove the invading forces out of Angola. This victory marked a turning point in the African anti-colonial and anti-apartheid struggles. The defeat of the apartheid army on the battlefield shattered the myth of white invincibility and emboldened liberation movements across the continent. The significance of Cuba’s action was not lost on the African continent. The World, a Black South African newspaper, captured the moment: “Black Africa is riding the crest of a wave generated by the Cuban success in Angola. Black Africa is tasting the heady wine of the possibility of realizing the dream of ‘total liberation."

Operación Carlota would last more than fifteen years. More than 400,000 Cuban soldiers, teachers, doctors, engineers, and workers served in Angola in various capacities during the mission. More than 2,000 Cubans lost their lives defending Angola’s sovereignty and supporting the right of the peoples of southern Africa to self-determination and freedom. This long struggle culminated in 1987–88 at Cuito Cuanavale, where combined Cuban and Angolan forces dealt a decisive defeat to the apartheid South African military. The 1987-88 military reversal in Angola constituted a mortal blow to the apartheid regime. The battle of Cuito Cuanavale ended its dream (nightmare for the region’s peoples) of establishing hegemony over all of southern Africa as a means by which to extend the life of the racist regime. This defeat on the ground forced South Africa to the negotiating table, resulting in Namibian independence and dramatically hastening the end of apartheid. Yet Cuba’s extensive and crucial role in the struggle against apartheid, and the broader regional war of terror waged by the apartheid regime that set the context for Cuba’s intervention, remain virtually unknown in the West. This extraordinary example of anti-imperialist solidarity remains largely erased from mainstream historical memory.

Apartheid South Africa’s War of Terror

Equally forgotten is the apartheid state’s regional war of terror—waged in Namibia, Angola, Mozambique, and beyond—which made Cuba’s intervention not only necessary, but historic. The struggle for and against apartheid unfolded both inside and beyond South Africa’s borders. Determined to secure and entrench its regional dominance, the apartheid regime waged war across southern Africa. Indeed, far more people—tens, if not hundreds, of thousands—lost their lives outside South Africa than within it. As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission observed, “the number of people killed inside the borders of the country in the course of the liberation struggle was considerably lower than those who died outside.” The human toll was staggering, between 1981 and 1988 alone an estimated 1.5 million people were killed directly or indirectly, among them 825,000 children.

Cuban involvement in Southern Africa has been repeatedly dismissed as surrogate activity for the Soviet Union. This insidious myth has been unequivocally refuted. John Stockwell, the director of CIA operations in Angola during and in the immediate aftermath the 1975 South African invasion, in his memoir, In Search of Enemies: A CIA Story, stated “we learned that Cuba had not been ordered into action by the Soviet Union. To the contrary, the Cuban leaders felt compelled to intervene for their own ideological reasons.” In his acclaimed book, Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington and Africa, 1959-76, Piero Gliejeses demonstrated that the Cuban government – as it had repeatedly asserted – decided to dispatch combat troops to Angola only after the Angolan government had requested Cuba’s military assistance to repel the South Africans, refuting Washington’s assertion that South African forces intervened in Angola only after the arrival of the Cuban forces and; the Soviet Union had no role in Cuba’s decision and were not even informed prior to deployment. In short, Cuba was not the puppet of the USSR. Even The Economist magazine (no friend of Cuba) in a 2002 article, acknowledged that the Cuban government acted on its “own initiative.”

That Cuba could act on its own initiative, independent of the great powers, was not only an anathema to Washington but also inconceivable. In 1969 Henry Kissinger, then National Security Advisor and later US Secretary of State, expressed characteristic chauvinism: “Nothing important can come from the South. History has never been produced in the South. The axis of history starts in Moscow, goes to Bonn, crosses to Washington, and then to Tokyo. What happens in the South is of no importance.” That Cuba—a poor “Third World” Latin-African nation—could act independently and shape history enraged Kissinger. At his behest, the Pentagon drew up extensive military plans in 1975–1976 to punish the island for defying the imperial order and its racist hierarchy. These plans, ranging from naval blockade to invasion, were seriously debated at the highest US levels, illustrating the dangers Cuba faced and accepted in defending Angola.

Paying Humanity’s Debt to Africa

The Cuban leadership justified the military missions in southern Africa as both defending an independent country from foreign invasion and repaying a historical debt owed by Cuba to Africa. Fidel Castro frequently invoked Cuba’s historical links to Africa. On the fifteenth anniversary of the Cuban victory at Playa Girón (Bay of Pigs), he declared that Cubans “are a Latin-African people.” The late Jorge Risquet, Havana’s principal diplomat in Africa from the 1970s to 1990s), was also unambiguous in explaining Cuba’s military intervention in terms of Cuba’s obligations to Africa, and this linkage resonated especially with black Cubans, who were able to make a symbolic connection with their African roots. As scholar Terrence Cannon for many blacks fighting in Angola was akin to defending Cuba except that the fight was “this time in Africa. And they were aware that Africa was, in some sense, their homeland.” Reverend Abbuno Gonzalez underscored this connection: “My grandfather came from Angola. So, it is my duty to go and help Angola. I owe it to my ancestors”. General Rafael Moracen echoed this sentiment and the words of Amilcar Cabral: “When we arrived in Angola, I heard an Angolan say that our grandparents, whose children were taken away from Africa to be slaves, would be happy to see their grandchildren return to Africa to help free it. I will always remember those words

Today, thousands of Cuban medical personnel provide essential services across dozens of African countries. In 2014, Cuba made a decisive contribution to the fight against the Ebola epidemic in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, sending the largest medical mission of any country.” More than 450 Cuban doctors and nurses—selected from over 15,000 volunteers—travelled to West Africa to stand alongside its peoples in the struggle against Ebola. As Cuba’s ambassador to Liberia, Jorge Lefebre Nicolas, affirmed: “We cannot see our brothers from Africa in difficult times and remain there with our arms folded.” At the 16 September 2014 United Nations Security Council meeting, Cuban representative Abelardo Moreno underscored: “Humanity has a debt to African people. We cannot let them down.” Even the Wall Street Journal acknowledged: “Few have heeded the call, but one country has responded in strength: Cuba.” Nevertheless, as Cuba specialist John Kirk notes, Cuba’s medical internationalism remains one of “the world’s best-kept secrets.”

Commemorating the anniversary of Operación Carlota is not simply an act of historical recovery. Fifty years on, Operación Carlota reminds us that the fight for African independence remains as urgent as ever. In a time when the struggle for authentic African independence and sovereignty is again under threat—from neocolonial economic domination, foreign military interventions, and resource plunder—it serves as a reminder of the possibilities of principled internationalism, solidarity, and collective liberation.

* Professor Isaac Saney is a Black Studies and Cuba specialist at Dalhousie University and coordinator of the Black and African Diaspora Studies program.