Is Normalisation With Cuba Irreversible?

Peter Kornbluh, The Nation | Thursday, 7 April 2016 | Click here for original article

That was one of Obama’s goals in his recent trip—and he made huge progress, charming the Cuban public and establishing a rapport with Raúl Castro.

The day after President Obama ended his historic trip to Havana, Cubans turned on their TV sets and watched his surprise guest appearance in a skit on the popular weekly show Vivir del Cuento (Live by Your Wits). The show’s star, Pánfilo—a character created by Cuban comedian Luis Silva—is playing dominoes in his humble apartment against two friends, complaining that he needs a teammate. Lo and behold, the president of the United States walks in. “¿Qué bolá?” Obama says, Cuban slang for “What’s happening?” After chanting “Obama, Obama, so nice you came to Havana,” Pánfilo asks the president how his visit is going.

“It’s been excellent!” Obama tells him. “The people have been wonderful. The food has been excellent, [also] the music. The Cubans here have all treated my family so nicely. I’m very grateful, and I’m so excited to be able to make this trip.”

“An emotional moment!” Pánfilo agrees. “A time of mutual respect. We are so happy that [US-Cuba] relations are getting fixed…. And not only relations, but the streets also,” he adds slyly, referring to the government’s efforts to spruce up Havana before the American president’s arrival.

It was actually Obama’s second appearance on Vivir del Cuento; he’d taped a mock phone call with Pánfilo from the Oval Office for an episode that aired just before his arrival in Havana. The president’s cameos were quietly arranged by the US embassy, with Obama having final say over the proposed script sent from Havana to the White House.

Obama’s humorous chitchat with Pánfilo advanced a key goal of his trip: direct engagement with the Cuban populace. His deft use of president-to-people diplomacy proved to be the most successful accomplishment of his three-day visit. “He is a person who knows how to speak without offending,” one taxi driver commented. “Unlike all the previous presidents.”

OBAMA’S AGENDA

Obama came to Cuba with an ambitious agenda. In addition to forging a direct and positive connection with the Cuban public, he wanted to establish a rapport with President Raúl Castro and mobilise economic, cultural, and political forces in the United States in support of his commitment to “write a new chapter” in US-Cuba relations. The president intended his trip, notes American University professor William LeoGrande, to be “a bold stroke aimed at accelerating the process of normalisation and making his policy of engagement irreversible.”

The timing, itinerary, and presidential entourage were all designed to advance that goal. By going now, rather than waiting until he’s a lame duck after the November election, Obama will have more time to use the power of the presidency to deepen normalisation. The president’s schedule included formal and informal bilateral meetings with Raúl Castro; forums with Cuban entrepreneurs and human-rights and democracy advocates; and opportunities to engage Cuban society at large—through TV and radio, as well as by attending a baseball game with some 50,000 Cuban fans.

Along with his wife and daughters, Obama was accompanied by a large bipartisan congressional delegation as well as CEOs and VIPs from major businesses like Google, PayPal, and Airbnb. His entourage also included politically influential Cuban-American businesspeople from Miami who have been converted from diehard backers of regime change to avid proponents of engagement. Most prominent among them was Carlos Gutierrez, who served as secretary of commerce during George W. Bush’s second term. Gutierrez predicted to reporters in Cuba that, in the wake of Obama’s trip, US business interests would “become more active” in pushing the GOP-led Congress to lift the US embargo.

In the months before Air Force One landed at José Martí International Airport, White House negotiators, led by Deputy National Security Adviser Ben Rhodes, worked with their Cuban counterparts to script the summit. Their agreement included two opportunities for Obama to talk directly to a national audience via television and radio: a press conference at the Palacio de la Revolución following his private meeting with Raúl Castro on March 21, and a speech the next day at the venerable Gran Teatro—the same venue where Calvin Coolidge, the only other US president to visit Cuba, had addressed the Cuban people in 1928.

The press conference proved to be the most uncomfortable encounter of the trip. Unlike his rhetorically gifted older brother Fidel, Raúl seldom speaks in public; indeed, nobody in Cuba could recall a time when he had answered questions from the media. But after Obama’s repeated requests, Castro agreed at the last minute to participate. According to their apparent agreement, after their opening statements, Obama would take two questions from US reporters, while Castro would respond to a single question from a Cuban reporter.

But the White House put Castro in the spotlight by picking Jim Acosta, CNN’s aggressive Cuban-American White House correspondent, to ask the first question. Instead of one question to Obama, Acosta asked three, and he posed four to Castro as well, pressing him on human rights and political prisoners. The press conference will be remembered for Castro’s defensive declaration—“Political prisoners? Show me a list and I will free them”—as well as his failed attempt to raise Obama’s hand in a joint salute when it ended. Pictures of that awkward moment provided “the perfect depiction,” as Jon Lee Anderson described it in The New Yorker, “of two leaders who represent nations that were once fierce enemies and have yet to figure out how to become fast friends.”

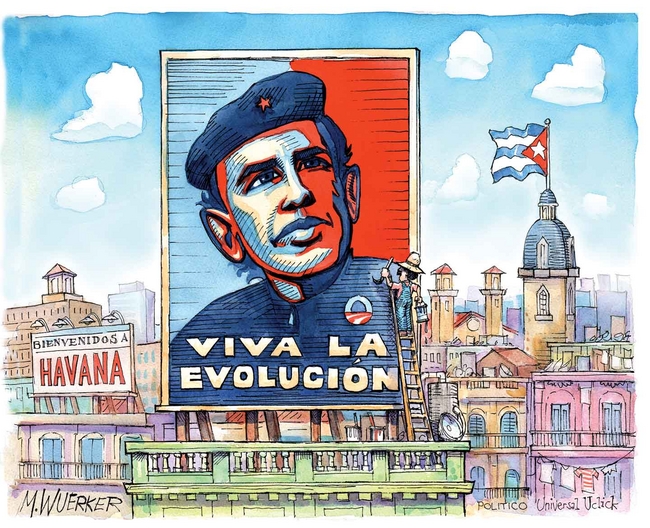

In his speech at the ornate and beautifully restored theater the next day, Obama presented his “change you can believe in” arguments to both the Cuban people and government. Drafted by Rhodes, the president’s address was carefully constructed to acknowledge Cubans’ pride in their revolutionary accomplishments and their legitimate national-security concerns about the history of US aggression, while voicing the president’s own hopes for Cuba’s socioeconomic and political evolution and improved US-Cuba relations in a nonimperious tone.

“Cuba has an extraordinary resource: a system of education which values every boy and every girl,” Obama noted at one point in his speech. In a compliment to Cuba’s international medical brigades, he said, “No one should deny the service that thousands of Cuban doctors have delivered for the poor and suffering” around the world.

Obama used the speech as an opportunity to address younger Cubans directly. “Many suggested that I come here and ask the people of Cuba to tear something down,” he said. “But I’m appealing to young people of Cuba who will lift something up, build something new,” To applause, Obama spoke in Spanish: “El futuro de Cuba tiene que estar en las manos del pueblo cubano.”

“And to President Castro,” Obama continued, looking directly at the Cuban leader, who was seated with other high-ranking members of the politburo, “I want you to know, I believe my visit here demonstrates you do not need to fear a threat from the United States.” While not apologizing for the country’s past acts of aggression, Obama owned up to the historical US efforts “to exert control over Cuba.” Before the revolution, he conceded, “some Americans saw Cuba as something to exploit, ignored poverty, enabled corruption.” But the era of attempts to control and exploit was over, he vowed. “I’ve made it clear that the United States has neither the capacity nor the intention to impose change on Cuba. What changes come will depend on the Cuban people.”

In his conclusion, Obama made an overt plea to lift “the shadow of history” from US-Cuba relations and move forward. “The history of the United States and Cuba encompasses revolution and conflict; struggle and sacrifice; retribution and, now, reconciliation. It is time now for us to leave the past behind. It is time for us to look forward to the future together—un futuro de esperanza,” he said. “We can make this journey as friends, and as neighbors, and as family—together. Sí se puede.”

RAPPORT WITH RAÚL—AND FIDEL’S OPINION

On the street, Cuban citizens appeared enthusiastic about Obama’s offer of friendship. My informal poll of taxi drivers revealed unanimous support for the president’s visit, along with hope that normalised relations would improve the daily lives of the Cuban people. “We Cubans have a favourable opinion of Obama,” said one hotel receptionist. “He was respectful, intelligent, sophisticated, and spoke well.” A security guard at another hotel summed up Obama’s efforts to move forward: “Hay que recorder el pasado, pero no vivirlo,” he said: We need to remember the past, but not live in it.

But Obama’s message received a far less positive reception in Cuba’s state-controlled media, including the official Communist Party newspaper, Granma, and the leading news website, Cubadebate. Article after article challenged Obama’s sincerity, attacked him for minimising the history of US aggression against the revolution, and questioned whether he was using “soft power” to continue a policy of regime change. In an opinion piece titled “Obama the Good?,” one hard-line political scientist, Darío Machado Rodríguez, called Obama “probably the best and most capable person on hand today to mask the strategic objectives of North American imperialism.… There is no doubt: Obama is the soft and seductive face of the same danger.”

Whether Raúl Castro harbors the same suspicions remains unclear. At the press conference, he called Obama’s efforts to change US policy “positive but insufficient.” When the two met privately, Castro indicated, he pushed Obama to do more to “dismantle the bloqueo,” which remained “the most important obstacle to our economic development and the well-being of the Cuban people.”

But the distance and discomfort on display at the press conference seemed to have evaporated by the time the two presidents arrived at Latin American Stadium the following day to watch the exhibition baseball game between the Cuban national team and the Tampa Bay Rays. Castro brought his family, including his son Alejandro, a high-ranking officer in the Interior Ministry. Obama brought his family as well; his daughter Malia was seen chatting in Spanish with Castro as they waited for the first pitch. And the two leaders looked casual and comfortable sitting side by side behind home plate.

In a final—and unexpected—diplomatic gesture, Castro went to the airport and walked Obama from the VIP lounge to Air Force One as the American president ended his history-making trip. When the two shook hands, their body language suggested that Obama and Castro had indeed established a positive and useful rapport, which should help advance the normalisation process.

As Obama prepared his Cuban visit, reporters asked repeatedly whether he would meet with former president Fidel Castro, the leader of the Cuban Revolution. At a briefing for the White House press corps in Havana, Rhodes explained that neither the Cubans nor Obama’s team had raised the possibility of such a meeting. But during an interview with ABC News halfway through the trip, Obama expressed his interest, assuming Fidel’s health permitted. “I’d be happy to meet with him,” Obama said, “as a symbol of the…closing of this Cold War chapter in our mutual histories.”

Although the president traveled to Cuba at the invitation of Raúl Castro, in many respects the trip was the culmination of more than a half-century of effort by Fidel to convince Washington to respectfully accept the Cuban Revolution. As William LeoGrande and I report in our book, Back Channel to Cuba, Fidel Castro quietly reached out to one president after another to improve relations. “I seriously hope that Cuba and the United States can eventually sit down in an atmosphere of good will and of mutual respect and negotiate our differences,” Castro stated in one secret message to Lyndon Johnson in early 1964. Obama’s “sit-down” with his brother Raúl would seem to have fulfilled that hope.

Yet six days after Obama departed Havana, Fidel delivered a decidedly negative judgment on his visit. In a 1,560-word missive published on state news websites and in official Communist Party newspapers under the title “Hermano Obama” (Brother Obama), Fidel declared that Cuba, a “dignified and selfless” country, did “not need the empire to give us anything.” Referring to Obama sardonically as “our illustrious guest,” Castro dissected Obama’s speech at the Gran Teatro and excoriated him for failing to adequately address the accomplishments of the Cuban Revolution, as well as the very distinct histories of the two countries. Fidel made his skepticism and continued distrust crystal clear. Obama, he argued, “uses the most sweetened words to express: ‘It is time, now, to forget the past, leave the past behind, let us look to the future together, a future of hope.’” Upon hearing those words spoken by a US president after almost 60 years of economic blockades and mercenary attacks, Fidel noted, “I suppose all of us were at risk of a heart attack.”

To be fair, Obama never said it was “time to forget the past”; in fact, he invoked it repeatedly. “The simple point he was making is that we need not be imprisoned by the past,” Rhodes noted in an exclusive interview with The Nation. “And given that we are working to normalize relations, the decision has clearly been taken to leave that past behind and focus on the future that we can build.”

WHAT’S NEXT?

What kind of future will Washington and Havana be able to build before Obama leaves office—and can the normalization process overcome the residual conflicts from the past? These are key questions for both nations. For example, in a move that threatened to undercut the president’s entire message a mere two days after he’d left Cuba, the State Department initiated a small, three-year $750,000 program enabling Cuban students to intern at NGOs in the United States to support Cuban civil society. The announcement drew an understandable response in the Cuban state media: “State Department project appears suspiciously like an infiltration plan,” read the headline on Cubadebate, over a large photograph of a Trojan horse.

With the Obama era coming to an end, Cubans (along with the rest of us) are naturally concerned about what will follow. A huge transition is also approaching in Cuba: Raúl Castro has said that he will step aside in 2018. It remains to be seen if Fidel’s negativity about Obama’s trip—and, by extension, normalisation with the United States—will have an impact on the Communist Party Congress this April, which will set new priorities for the country’s economic modernization and future leadership.

But Cuba’s transformation is clearly irreversible. The free concert by the Rolling Stones just three days after Obama left was yet another example of Cuba’s complete integration into the global cultural economy. As Mick Jagger told a rollicking audience of more than 500,000 Cubans when the Stones rocked Havana on March 25, “I think the times are changing!”

In Washington, advocates of normalisation are now building on the momentum of Obama’s trip to consolidate economic and cultural bridges. The president’s recent decision to ease restrictions on travel to Cuba will surely bring about a vast increase in US visitors—each one of them a potential lobbyist for passing the Freedom to Travel to Cuba Act, which would lift all restrictions on American travelers, whether for “educational” tourism, as regulations now require, or as simple vacationers.

Moreover, with US companies like Google, Starwood Hotels and Resorts, and Airbnb establishing a corporate foothold in Cuba, there will be escalating pressure on Republican leaders to allow a vote to end, once and for all, the trade embargo. Even Alan Gross, who spent five years in a Cuban prison for his work on the US government’s quasi-covert, Bush-era “democracy promotion” programs, has called on Congress to “grow a pair” and “get over the failure of the embargo by lifting it.”

In both countries, it’s understood that the road to rapprochement is a long one. “To destroy a bridge is easy and takes little time,” Raúl Castro told reporters during his Havana press conference with Obama. “To reconstruct and strengthen it is a much longer and more difficult endeavor.” In his speech to the Cuban people, Obama echoed that sentiment. Overcoming the past and building normal relations “won’t be easy,” he said.

“No es fácil,” the president told Pánfilo. Then again, as Pánfilo responded more optimistically: “It isn’t easy, but it isn’t difficult either!”