Under Fidel Castro, Sport Symbolised Cuba’s Strength and Vulnerability

New York Times | Tuesday, 29 November 2016 | Click here for original article

By JERÉ LONGMANNOV. 27, 2016

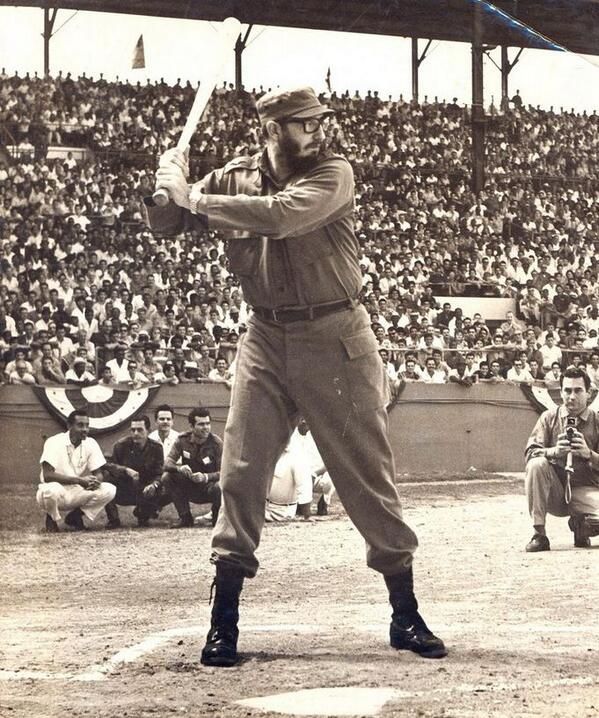

On July 24, 1959, months after coming to power, Fidel Castro took the mound at a baseball stadium in Havana to pitch an exhibition for a team of fellow revolutionaries known as Los Barbudos, the Bearded Ones.

He pitched an inning or two against a team from the Cuban military police and, by some accounts, struck out two batters.

“He threw a few pitches, people were swinging wildly and letting themselves be struck out by the Leader,” said Roberto González Echevarría, a native of Cuba who is a literature professor at Yale and the author of “The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball.”

Mr. Castro, who died Friday at 90, also avidly followed Havana’s Sugar Kings of the International League, a Class AAA team in the Cincinnati Reds’ farm system from 1954 to 1960. He went to some games because he was a fan and “he liked being on TV,” Mr. González Echevarría said.

The persistent notion that Mr. Castro’s fastball had made him a potential big league prospect has long been debunked by historians. By many accounts, his primary sport as a schoolboy was basketball. He was tall, at 6-foot-2 or 6-foot-3, and he told the biographer Tad Szulc that the anticipation, speed and dexterity required for basketball most approximated the skills needed for revolution.

Yet it was primarily baseball, along with boxing and other Olympic sports, that came to symbolise both the strength and vulnerability of Cuban socialism.

Successes in those sports allowed Mr. Castro to taunt and defy the United States on the diamond and in the ring and to infuse Cuban citizens with a sense of national pride. At the same time, international isolation and difficult financial realities led to the rampant defection of top baseball stars, the decrepit condition of stadiums and a shortage of equipment.

The former Soviet bloc and China also acutely understood the value of sporting achievement as propaganda, but there seemed to be some fundamental differences in Mr. Castro’s Cuba.

For one thing, Cuba under Mr. Castro promoted mass sport, not simply elite sport. About 95 percent of Cubans have participated in some form of organised sport or exercise, from children who start physical education classes at age 5 to grandmothers who gather to practice tai chi, said Robert Huish, an associate professor at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who has studied Cuban sport, health and social programs.

Secondly, “I think Fidel Castro legitimately liked sports,” said David Wallechinsky, the president of the International Society of Olympic Historians. “One got the sense with East Germany, for example, that it really was a question of propaganda and that government officials didn’t have that obsession with sport itself that Fidel Castro did.”

Whatever hardships they endured, Cubans could take pride in their sports stars.

As Javier Sotomayor, the only man to clear eight feet in the high jump, soared to his records in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Cubans for a time marked the height of his jumps in their doorways, according to Robert Huish, an associate professor of international development studies at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, who has studied Cuban sport, health and social programs.

“There was a real effort to connect nationalistic pride to athletic achievement,” said Mr. Huish, who was scheduled to make his 42nd trip to Cuba on Monday. “Boxing became a really important factor in that. You would hear how it was connected to revolution and how socialism and having universal access to sport meant that the victory of the boxer is really everyone’s victory.”

Teófilo Stevenson, a three-time Olympic heavyweight boxing champion from 1972 to 1980, once famously explained why he had turned down a chance to sign a professional contract and perhaps to fight Muhammad Ali, saying, “What is a million dollars’ worth compared to the love of eight million Cubans?”

The idea that sports “were healthy and good for developing bodies,” Mr. González Echevarría said, derived from the American role in helping to establish Cuba’s educational system while occupying the country from 1898 to 1902 after the Spanish-American War.

In “Castro’s Cuba, Cuba’s Fidel,” a biography by the American photojournalist Lee Lockwood, Mr. Castro spoke little of baseball, instead stressing his long love for basketball, chess, deep-sea diving, soccer and track and field. “I never became a champion,” he told Mr. Lockwood, adding, “but I didn’t practice much.”

In 1946, an F. Castro was listed in a box score as having pitched in an intramural game at the University of Havana, where Fidel Castro attended law school, though González Echevarría said he could not confirm it was the future leader.

The only known photographs of Mr. Castro in a baseball uniform were taken while he played for Los Barbudos, the informal revolutionary team, Mr. González Echevarría said. Mr. Castro was never scouted by the major leagues, Mr. González Echevarría said, and the notion that Mr. Castro was once a promising pitcher “is really a lie.”

Instead, Peter C. Bjarkman, a baseball historian, argues that Mr. Castro’s post-revolutionary identification with baseball derived from two factors: One, an acknowledgment of the entrenched popularity of a sport played in Cuba since the 1860s and as popular there as soccer was in Brazil. And two, a stoking of revolutionary zeal at home and a forging of propaganda victories abroad.

While Mr. Castro staged some exhibitions and played some pickup games after coming to power, a primary objective was to bedevil the United States in a “calculated step toward utilising baseball as a means of besting the hated imperialists at their own game,” Mr. Bjarkman wrote in an article for the Society for American Baseball Research.

Mr. Castro banned professional sports in Cuba in 1961, and several years later, said, “Anybody who truly loves sport, and feels sport, has to prefer this sport to professional sport by a thousand times.”

His strategy worked for decades as Cuba played baseball against mostly amateur competition, or non-major leaguers, winning 18 championships in the Baseball World Cup from 1961 to 2005 and three Olympic gold medals from 1992 to 2004.

But the collapse of the Soviet Union (and later Venezuela’s oil economy), cost Cuba its financial benefactors. And its dominance began to ebb amid rampant defections of top Cuban players and the growing inclusion of professionals from other nations in international baseball tournaments.

Cuba won only one of the three Olympic tournaments held after 1996, before baseball was discontinued for the 2012 London Games (it will return at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.) And Cuba has yet to win the World Baseball Classic, a quadrennial tournament that began in 2006 and features major leaguers.

Meanwhile, the American trade embargo, still in place even though the two countries have begun to normalise relations, has left Cuba with poor sports facilities, including some pools with no water; fewer night baseball games because of the cost keeping the lights on; games halted in some stadiums until fans can retrieve foul balls; and a leaky roof and soaked mats at the national wrestling centre.

In 2013, Cuban officials took a more pragmatic approach to professionalism, allowing athletes to compete for earnings and to play in other countries (though not in Major League Baseball). Cuban coaches are also being exported to other countries in exchange for hard currency. The athletes keep 80 percent of their winnings and agree to compete for Cuba in international competitions.

Antonio Castro, a son of Fidel Castro and a vice president of the International Baseball Federation, told ESPN in 2014 that Cuban players should be permitted to play in the Major Leagues and be able to return to Cuba “without fear.”

“Then no one loses,” Antonio Castro said. “And they don’t have to be separated from their family, from their friends.”

But after President Obama attended an exhibition baseball game in Havana in March as the first sitting American president to visit Cuba since the 1959 revolution, Fidel Castro threw a brushback pitch.

In a column, he criticised renewed relations between the two countries, writing, “We don’t need the empire to give us anything.”