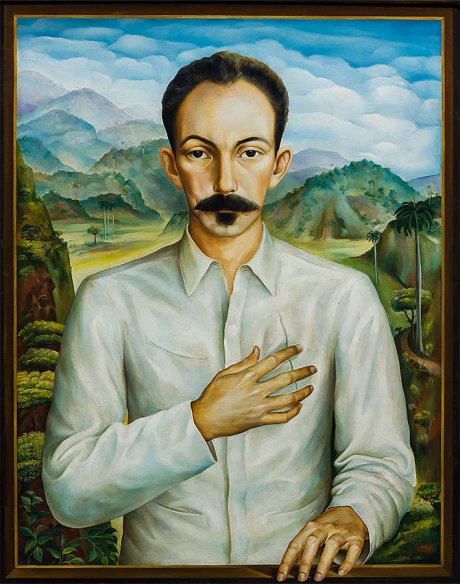

José Martí - Cuba’s hero

Cuba Sí | Friday, 27 January 2023

2023 is the 170th anniversary of the Cuban independence hero José Martí’s birth. Stephen Wilkinson of the International Institute for the Study of Cuba explains why Martí is so important.

“I come from all places and to all places go”

José Martí

Every visitor to Cuba who lands in Havana arrives at José Martí International Airport. If the visitor is observant, as they walk through the streets, they will notice that outside the entrance to every school stands a bust of a moustachioed slightly balding man. That, too, is José Martí, and when the visitor takes the tour to Revolution Square, where all the great rallies are held, they will see that it is presided over by a giant statue of this man whom Cubans call their ‘apostle’. If the traveller is lucky enough to scale the country’s highest mountain, el Pico Turquino, they will find a bust of Martí at the peak. So who was Martí and why is he so important?

Primarily, Martí is remembered as the architect of the last Cuban War of Independence against Spain, and as a martyr in that struggle, for he died in the early months of fighting in 1895 at the age of just 42. In such a short life, Martí accomplished astonishing things. The possessor of a truly exceptional intellect, he was a writer and activist, philosopher and a considerable poet, regarded as one of the greatest modernist poets in the Spanish language. Immensely popular, the words of his autobiographical poem, Los versos sencillos (the simple verses), provide the lyrics to the anthem Guantanamera. He was also a journalist, orator and polemicist, an advocate for the rights of women and black people, and for children. Martí’s collected works run to 25 volumes. He was the inspiration for generations of revolutionaries struggling for Cuban independence and, more than Marx, the prime motivator for Fidel Castro and his followers in their rebellion against the corrupt and venal rule of the dictator Fulgencio Batista.

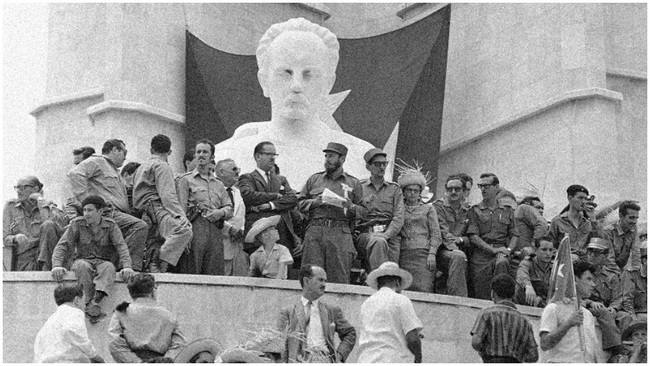

Indeed, Castro’s initial attempt against Batista in Santiago de Cuba on the 26 July 1953, took place precisely in the centenary year of Marti’s birth. The group led by Castro called themselves ‘the centenary generation’ to mark the fact, and their manifesto, written by Castro himself, made reference to Martí and the shame he would have felt on seeing what Cuba had become under Batista’s rule. After the attack, when he was tried, Castro invoked the hero in his famous defence speech, ‘History will Absolve Me’, where he quoted Martí at length.

There is no doubt that Cuba’s unique twentieth century revolutionary process owes itself to the thoughts and ideas of this nineteenth century man who spent more of his life in exile outside the island than he did within it. Indeed, Martí’s influence on the Cuban revolutionary ideology is so important that it is possible to argue that without his example and legacy of wisdom and sage advice, the Revolution would not have survived the collapse of the Soviet Union and most certainly, without him, Cubans’ antipathy towards the politics of the United States would not be so firm.

Ironically enough for a Cuban patriot, Martí came from a loyal Spanish family. His father was a sergeant in the army and part of Martí’s childhood was actually spent in Spain. Later, his father became a policeman in Havana. Rather than his father, Martí learned most from his schoolteacher, Rafael María Mendive who was a poet and supporter of Cuban independence. Martí was at school and under Mendive’s influence when the first war of independence broke out in 1868. The young Martí, aged sixteen, started his first newspaper, Patria Libre, and published poems in support of the rebels. Tragedy ensued. Mendive was exiled to Spain and Martí was arrested for seditious activity. He was sentenced to six years hard labour and sent to break stones in a quarry outside Havana. The sores he contracted from the shackles around his ankles affected him for the rest of his life. Thankfully, through the entreaties of his mother, his father was able to use his influence to get his son released and sent to exile in Spain on the condition he did not return to the island. So, at the age of 18, Martí arrived in the heady atmosphere of revolutionary Madrid.

There he studied law and later transferred to Zaragoza , where he graduated in 1874. In Spain, he became an adherent of the philosophy of Karl Christian Krause, which was popular among the Spanish avante garde at the time. Much of Martí’s own thought owes itself to this humanistic philosophy that seeks to place humankind in harmony with nature. Martí was already writing poetry, articles and plays, inspired by Krausist ideas and on the theme of Cuban independence. In 1895, he moved to Mexico and there he cultivated his literary style, writing a successful play: Amor con amor se paga (Love is paid with love) becoming a well-known figure. He then moved to Guatemala, where he worked as a university professor, but in 1878, when Spain pardoned those who had fought in the war, he returned to Cuba. In Havana, he met his long-time collaborator, the black writer Juan Gualberto Gómez, with whom he would work closely in the organisation of a new revolutionary party. Martí’s stay didn’t last long, within a year the Spanish arrested him again and sentenced him to hard labour in North Africa, However, he escaped and managed to flee to New York City, where he arrived in 1880. He was 27.

Martí resided in New York for almost 15 years and lived by his writing. He came to know the United States very well, serving as the foreign correspondent for a variety of South American newspapers. He wrote movingly about the plight of immigrants, blacks, Native Americans and workers and was horrified by the racial violence he witnessed at a lynching. He was also shocked by the disdain with which people in the United States regarded those from the South. He said that they regarded the US as America “without thinking there might be another America” and he realised early that the US was on an expansionist path towards dominating the continent. This realisation inspired his most published essay: ‘Our America’, an ode to Latin American unity. In this work, Martí warns the South that the time is coming when it “will be approached by an enterprising and forceful nation that will demand intimate relations with her, though it does not know her and disdains her.” This would be “our America’s greatest danger.”

In exile, Martí worked tirelessly to organise a new Cuban independence party and prepare for another attempt at rebellion. He reunited the great figures from the previous war, Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo and raised money by speaking tours in Cuban émigré communities in Brooklyn and Florida. But as well as preparing for war, he also spent much time contemplating on the kind of place a free Cuba would be after victory was achieved. Unlike the United States, which he found hard and unjust, he wanted a Cuba, as he said that would be “for all and the good of all.”

This implied a profound commitment to racial harmony. Taking the lesson from the 1868-78 war, in which black and white Cubans fought together, Martí articulated a notion of Cubanness or Cubanidad, that transcended racial difference. Together with his friend Juan Gualberto Gómez, he advocated for a Cuba that would be an example to the world in terms of its inclusivity. Martí realised, too, that the independence of Cuba would have to take place in the face of US imperialism and could, if it were successful, act as a means to stop it. As a beacon of racial justice, the new Cuban republic would be an example to the world that would be in stark contrast to the United States and therefore a revolution for the whole of humankind.“My country is humanity”, he wrote.

This sentiment is captured most poetically in Martí’s last, unfinished, letter that was found in his belongings after his death in battle in 1895. Of all the many thousands of citations from his works that can be found adorning walls in Cuba, this passage is the one that is etched deepest in the minds of all Cubans:

"Every day now I am in danger of giving my life for my country and my duty…to prevent , by the timely independence of Cuba, the United States from extending itself across the Antilles and falling with greater weight upon the lands of our America… I have lived inside the monster. I know its entrails and my sling is that of David."

More than any other legacy, Martí’s prophesy about the United States and his biblical metaphor of Cuba being David against the Goliath of the North is perhaps the defining image that guarantees the resistance of Cubans today.

However, in order to understand the way Martí’s legacy works in Cuba, another passage from that same letter is perhaps more important. He notes that opposing the US had always been his intention, but he had been obliged to keep it secret as there are things “that have to be concealed in order to be attained.” Telling them would create obstacles that would be too great to overcome, he says. When the French journalist, Ignacio Ramonet, interviewed Fidel Castro, Fidel cited the passage verbatim and told Ramonet that these words were his inspiration in political strategy. Therefore, it is entirely possible (though we will never know for sure) that Castro followed this advice in keeping his socialism secret in the 1950s, so that he would not be labelled a Communist and enable him to attract the following of the middle and upper classes.

Whether or not he was a Marxist at the time, it is clear that Castro had been a disciple of Martí from his youth. In 1949, after a group of US sailors had caused a scandal by urinating on the statue of Martí in Central Park, Havana, Fidel led a group of students in a protest at the US embassy that was brutally put down by the police. Four years later, in his trial, when asked who was the intellectual author of the assault on the Moncada garrison, Castro replied: “Only José Martí, the Apostle of our independence.” People in the courtroom applauded. That same year, on the centenary of the Apostle’s birth, a woman, who would later become Fidel’s personal secretary, Celia Sánchez, raised the funds to put the bust of Martí on the peak of El Turquino. Shortly after their victory in 1959, Fidel led a group of students on a climb to the top of the mountain to lay a wreath on the statue. Climbing the Turquino to repeat the homage is a rite of passage for young militants still today.

Thus, Fidel and his followers were the heirs of Martí, they shared his vision and understood his importance in the hearts and minds of Cubans. They successfully channelled the power of Martí to inspire them to try and make real his dream of a better Cuba and a better world, free from US imperialism. The great Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén summed it up: Lo que Martí prometió, Fidel lo cumplió (What Martí promised, Fidel fulfilled). Truly, the revolution is Martí’s.

This article first appeared in the Winter 23 edition of Cuba Sí. Join the Cuba Solidarity Campaign today to receive Cuba Sí four times a year.

Further reading - Jose Martí Reader: Writings on the Americas.