The Monroe Doctrine: Two hundred years too long

Campaign News | Wednesday, 19 April 2023

President James Monroe

Francisco Dominguez on the history and development of the ‘doctrine’ that has been used as a justification for US intervention in Latin America for two centuries

In December 2023, the infamous Monroe Doctrine will be 200 years old. For some people, the name refers simply to a long and complex foreign policy document with constitutional status, but it is far more than that.

In his seventh annual message to Congress, US President James Monroe used six minutes of his hour-long speech to espouse his future plan for the continent, then in the midst of a war of liberation from Spanish colonial domination. This six-minute vision became known as the Monroe Doctrine.

By 1823 most of Latin America had successfully declared independence, and liberation armies, commanded by Simon Bolívar and other freedom fighters, were in the final stages of defeating a Spanish military counteroffensive. With Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo, the sale of Louisiana to the US in 1803 and the loss of Haiti following a slave rebellion in 1804, France’s American empire had already collapsed. These momentous developments offered rich pickings in the New World to ‘Perfidious Albion’ (a term that referred to Britain’s bad faith and duplicity in international relations).

Monroe Doctrine promoters believed that only by controlling the whole of the Western Hemisphere and the new republics would the US consolidate, expand and remove the threat from the European empires. The main threat to the US came from a substantially strengthened British empire that had Canada to its north, the strategic islands of the British West Indies to its south, and strong relations with Native American tribes. Furthermore, Cuban and Puerto Rican Creole oligarchies remained loyal Spanish colonies, allowing Spain to maintain a strong military presence in the Caribbean.

In Europe, the Holy Alliance, a coalition of European monarchies whose reactionary objective was to eradicate all traces of republicanism and liberalism in the Old World and Latin America, had plans to restore the American colonies to Spain. Consequently, to survive and develop the US needed to exert its rising influence over the Caribbean, Central America and the whole hemisphere, simultaneously helping to consolidate the new republics and keep the Europeans out.

In Britain, Foreign Secretary George Canning thought that British interests would be best served if not only were there no Spanish colonial restoration and other European powers were prevented from predatory incursions into former colonies, but also if the US did not gain hemispheric influence at the expense of Britain’s commercial relations with the new republics. He suggested to President Monroe that Britain and the US work together to keep the rest of Europe out of Latin America. Canning’s proposal would also have given Britain veto power over other hemispheric developments, including any US expansion southwards.

Unsurprisingly, Monroe ignored Britain’s request, and his ‘doctrine’ sent a stern warning to the foreign ministers of Europe that no part of Latin America could be considered for future colonisation by any European power, and any attempt at colonisation would be regarded as a hostile act against the US.

For Monroe, Jefferson, Adams and other presidents, the United States was an example for the world, and the Monroe Doctrine was a vehicle to promote US principles. As such it became the precursor of the ‘Manifest Destiny’, a term coined by journalist John O’Sullivan in his 1845 essay in support of annexing Texas. He argued: it is “the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent which Providence has given us for the development of the great experiment of liberty and federated self-government entrusted to us.” US leaders believed that given the virtuosity of its people and institutions, God had assigned the US with the duty to shape the rest of the continent and the world by expanding its dominion and spreading democracy and capitalism. Deeply racist, it posited the ‘civilising’ of indigenous peoples of all North and South America, including dispossessing the former from their lands – all predicated on Anglo-American racial superiority.

US territorial expansion, at the expense of indigenous lands and Mexico, was staggering. From the 13 original colonies in 1783 (1,100,00km2), after adding the Louisiana Purchase (2,140,000km2, 1803), Florida (170,310km2, 1819), Texas (695,596km2, 1838) and 55 per cent of Mexico’s territory (California, Nevada, Utah, Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico parts of Oklahoma, Kansas and Wyoming, 1,370,000km2, 1848), the US’s geographical size increased fourfold to 5,475,906km2. Ominously for Latin America’s future, the US used military means to annex Texas (Mexican-Texan War, 1834-36) and half of Mexico (Mexican-American War, 1845-48).

1823 also marked the year when annexationist and future president John Quincy Adams drew his famous ripe fruit analogy: “if an apple severed by its native tree cannot choose but fall to the ground, Cuba, forcibly disjoined from its own unnatural connection with Spain, and incapable of self-support, can gravitate only towards the North American Union.”

The US threatened war to prevent the transfer of Cuban sovereignty, and in 1823 former president Thomas Jefferson advised President Monroe to oppose, with all US means, most especially [Cuba’s] transfer “to any power by conquest, cession or in any other way”. The US strongly coveted the island, which was key to its commercial and military hegemony over the Caribbean.

Cuba was an exception to independence. Haiti’s revolution (1791-1804) had led Cuba to become the substitute world sugar supplier; therefore, it had imported large numbers of enslaved people to work in its expanding sugar economy. The numbers of enslaved people in Cuba rose from 44,000 in 1774 to nearly 370,000 by 1861; in 1841 the black population was greater than the white.

Following the example in Haiti, enslaved people mounted rebellions in Cuba in 1812, 1826, 1830, 1837, 1840, 1841 and 1843. Cuban elites concluded that independence might lead to not only the end of Spanish colonial domination, but also an end to the enslaved labour they relied on. The social forces required to dislodge peninsular elites could, as they had in Haiti, extend to displace the Creole oligarchy. In the circumstances, they preferred to remain a Spanish colony.

The expansion of the sugar economy drew Cuba closer to the United States rather than Spain. “By the 1840s, almost half of Cuban trade depended directly on North American markets and manufacturers,” says historian Louis A Perez in his book ‘Cuba, Between Reform and Revolution’. “Sugar, molasses, and hides went out, vital foodstuffs, sugar machinery, and, increasingly, [US] capital came in.”. In 1848 president James K Polk offered US$100 million to purchase the island. In 1854 President Franklin Pierce raised the offer to US$130 million.

Although many in the Cuban elite were not seeking independence, Spain was increasingly unable to protect its colony from rebellions, and the US was incapable of taking the island due to the domestic polarisation between slave and free states. Sections of the Cuban oligarchy thought annexation to the US would both make slavery survive and be the salvation of the sugar economy. However, following Spain’s abolition of slavery, Carlos Manuel de Céspedes, a Cuban landowner, freed the enslaved people on his land and sparked the first Cuban War of Independence (1868-78).

Despite intense pressure, President Ulysses Grant, who was strongly anti-slavery, accepted Cuban revolutionaries’ belligerent status but remained neutral. It would be entirely different in Cuba’s second War of Independence (1895-98). In 1898, President William McKinley declared war against Spain, ostensibly for having blown up the warship USS Maine and to help ‘liberate Cuba’, but in reality to prevent its independence.

Cuba’s revolutionary leader, José Martí, painfully aware of the US’s hegemonic intentions, believed Cuba’s timely independence would prevent the US “from extending itself across the Antilles and falling with greater weight upon the lands of our America.” Just when the Cuban rebels were about to succeed in 1898, with an army of 17,000 the US took military control of the island, defeated Spain, and, confirming Martí’s apprehension, went on to occupy Puerto Rico, extend the war against Spain to the Philippines (which it also occupied militarily), annexed Hawaii, and took the island of Guam.

The US military occupied Cuba until 1902 and let it have an independent government by imposing two hefty constraints before lifting the occupation: the Platt Amendment and two military bases (Guantánamo and the Isle of Pines). The Amendment – which was added to the new Cuban constitution – gave the US authority to intervene militarily in Cuba, as it did in 1906-09, 1912, and 1917-22; furthermore, it prohibited Cuba from signing any treaty with another foreign power.

President Theodore Roosevelt developed the Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny into his infamous Corollary: “in the Western Hemisphere the adherence of the United States to the Monroe Doctrine may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.”

Roosevelt’s foreign policy method was “speak softly, but carry a big stick.” His Corollary would lead the US to break Panama from Colombia (1903), to the military occupations of Nicaragua (1912-1933), Haiti (1915-34), Dominican Republic (1916-1924), and to several more in Central America and the Caribbean. With the Cold War, the US’s most important interventions were Guatemala (1954), Dominican Republic (1961), Cuba (Bay of Pigs 1961), Brazil (1964), Bolivia (1971), Chile (1973), Argentina (1976), Nicaragua (1979-1990), Grenada (1983), El Salvador and Guatemala (1980s) and Panama (1989). Literally hundreds of thousands of people were butchered by these US Monroist incursions.

Until the Cuban Revolution, Cuba was a de facto US colony. Speaking to a US Senate Committee in 1960, former US ambassador to Cuba Earl E T Smith said: “Until Castro, the US was so overwhelmingly influential in Cuba that the American ambassador was the second most important man, sometimes even more important than the Cuban president.”

By 1959, US direct investment in electric power and the telephone service was 90 per cent; raw sugar production, 37 per cent; commercial banking, 30 per cent; public service railways, 50 per cent; petroleum refining, 66 per cent; insurance, 20 per cent; and nickel mining, 100 per cent. Furthermore, the island had become a paradise for gambling, the Mafia and prostitution, and, being a single-crop economy, large sections of its population endured poverty, malnutrition, illiteracy and chronic unemployment.

The Monroe Doctrine with its enhancements, the Manifest Destiny and the Roosevelt Corollary, is a US template for hegemony. The Cuban Revolution broke the vicious cycle of US domination in the island, but US Monroist aggression continues as proved by 61 years of blockade and ruthless US attacks on progressive governments in the 21st century.

In 2019, the fanatical cold warrior John Bolton claimed that the “Monroe Doctrine is alive and well.” He is right. US racism, exploitation and military interventions– with their horrible trails of violence, exploitation, poverty, destruction and death all across Latin America and the world – are, appallingly, very much alive. Humanity has endured two hundred years too many of this damn ‘doctrine’.

Dr Francisco Dominguez is academic and a specialist on Latin America’s contemporary political economy, and an executive committee member of the Cuba Solidarity Campaign.

This article originally appeared in CubaSi magazine.

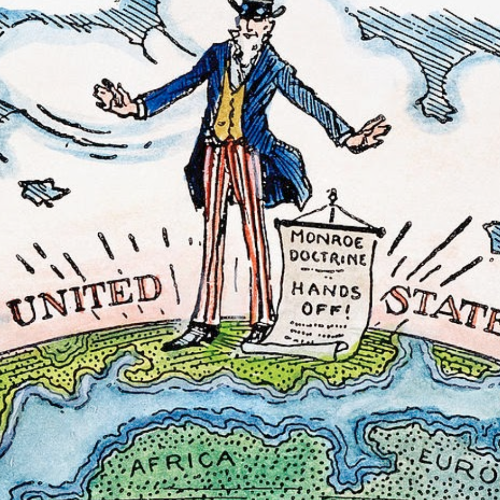

An early twentieth century US cartoon on the Monroe Doctrine

Monument to Carlota Lucumí, leader of the 1843 slave rebellion at the Triumvirato Sugar Mill in Matanzas